(November 4, 2022: This is the first in a series of posts I’ll be publishing in the coming weeks about the background to an art exhibition opening at the museum at Kibbutz Ein Harod. The show is a retrospective of the works of five artists from one extraordinary family: the Abu Shakras of Umm al-Fahm.

I’m an American-born journalist who has been living in Israel since 1987. I’m Jewish, but I have long been interested in learning about the country’s Palestinian population. They have contended with countless challenges, which continue to this day, but this is their home, and they aren’t going anywhere, although that is something that some parts of the Jewish population still don’t understand.

To me, the Abu Shakras, their birthplace, and the art gallery in the city that’s associated with them, tell a story that goes beyond art. Call me naive, but I think that story can point a way forward to reconciliation among Israelis. Writing shortly after the November 1 election, I know how tempting it might be to think that “all is lost.” But this is our shared home, and we don’t have the option of losing faith. Maybe this newsletter will serve to provide readers with reason to be more hopeful. dbgiht@gmail.com)

• • •

If you’re reading this today, you can blame Yoko Ono. Well, sort of.

In 1999, the Japanese-born multi-media artist who is best known for being the widow of John Lennon (not to mention the one who many still blame for the breakup of his rock band), agreed to allow a traveling retrospective exhibition of her work to visit Israel. There, it was to be hosted by the Israel Museum, the country’s national museum of art and archaeology. Ono had a condition, though: If her show was going to appear in Jewish, west Jerusalem, on the hill across from the Knesset and Israel’s government offices, it had to be complemented by a show in “Palestine.” She was coming after all, in the spirit of peace and reconciliation.

In November 1999, the second intifada still a year in the future, and the semi-autonomy afforded to the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and Gaza, courtesy of the Oslo Accords, was still functioning, but the peace process was definitely foundering. Israel itself was divided – violently so: Yitzhak Rabin had been murdered four years earlier by a Jew for having signed those accords with Yasser Arafat, and Palestinians opposed to any agreement with Israel were subjecting it to regular suicide attacks, which became no less traumatic for Israelis even as they became more frequent.

The preceding summer, Ehud Barak had become premier, toppling the government of Benjamin Netanyahu (in his first, brief go-round as prime minister), but Israel’s most-decorated military officer would serve for only 20 months. In September of 2000, not long after he returned from Camp David, Maryland, where he and Arafat failed to reach agreement on a permanent peace plan despite the efforts of their host, President Bill Clinton, an outbreak of violence in Jerusalem developed into the intifada. That cycle of mutual, shocking violence carried on for the next four years, and for a brief time after its inception, it looked as if it might cross the border and turn into an all-out civil war between Palestinians and Jews.

In 1999, however, it was still possible to imagine “all the people living life in peace,” and Israelis and Palestinians moving between Jerusalem and, say, Ramallah, to visit joint Yoko Ono exhibitions. If that didn’t happen, it was because the West Bank didn’t at that time offer an appropriate and accessible venue that could host even a small exhibition of her works. Israeli curator Shlomit Shaked, however, came up with an alternative: Bring the auxiliary Ono show to the Umm al-Fahm Gallery of Art.

Umm al-Fahm is Israel’s third-largest Arab city, lying just inside the Green Line, as the border between the state and the West Bank is called. Its residents, who at the time numbered under 40,000, are Israeli citizens. Its art gallery had opened only three years earlier, and had the tiniest of budgets, but it had already made a name for itself as a serious venue for contemporary art. And it was committed to bringing together Jews and Arabs, both as artists and patrons. Now, by hosting a major celebrity, the independent, non-profit cultural institution in the most unlikely of locations became, overnight, known to the wider public.

And thus, shortly after the grand opening of the career-spanning show “Have You Seen the Horizon Lately?” in Jerusalem, another opening was held for the far-more-modest “Open Window” exhibition in Umm al-Fahm.

This was no small thing. Just a year earlier, hundreds of residents of the city had been wounded during demonstrations they mounted against a government decision to deny them access to farmland that had once been theirs. The fields, situated on the northern side of Highway 65, had been technically expropriated by the state decades earlier, but the authorities had allowed the owners to continue to work the land. In the summer of 1998, however, the state declared the land a military firing zone, thus putting it beyond the reach of the people who depended on it for their livelihood.

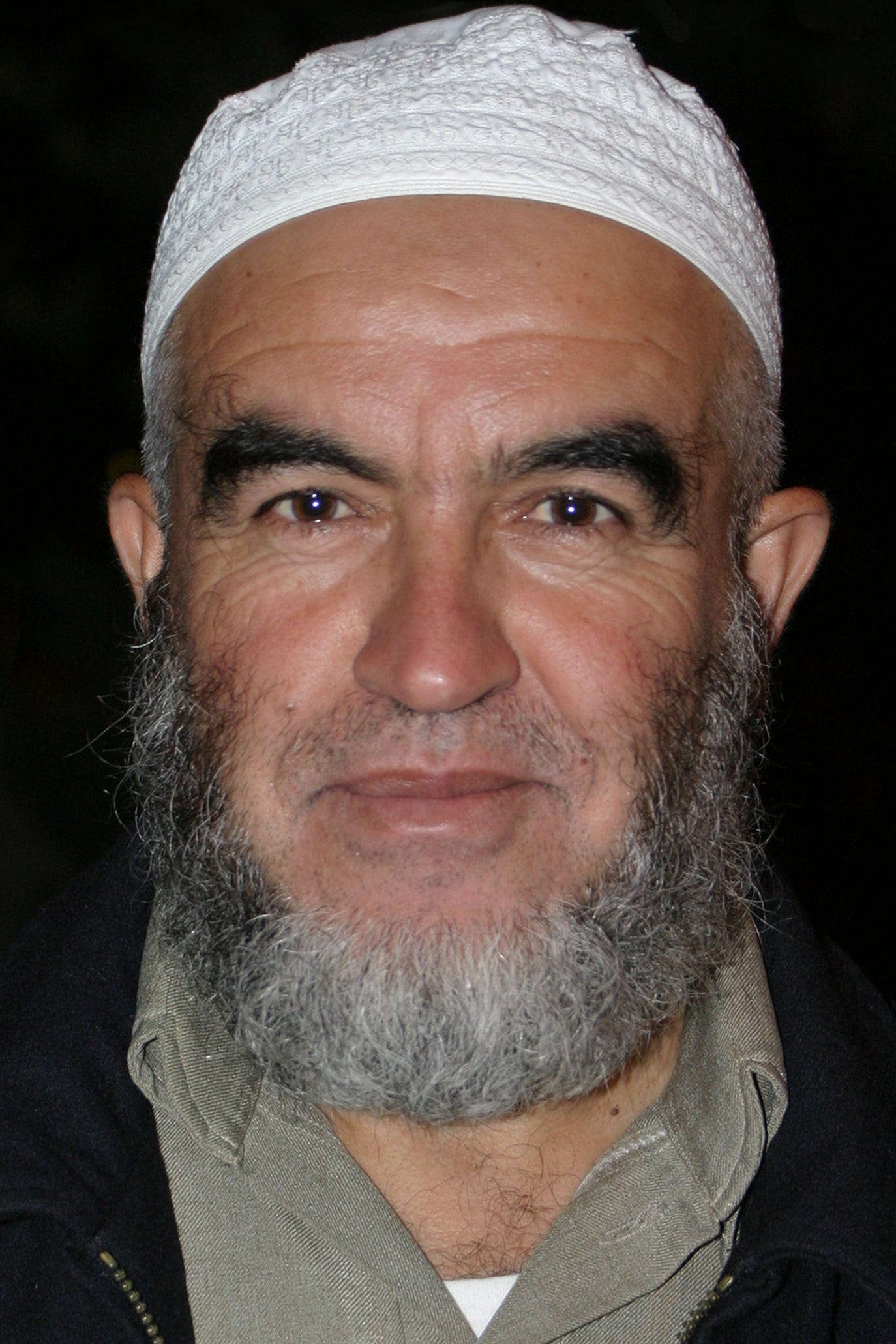

A group of Fahmawis set up a protest camp at the site, but after several weeks, members of the Police and Border Police came to remove them forcibly. The confrontation that ensued spilled across the four-lane highway that separates the area from the developed part of Umm al-Fahm, where members of the security forces chased the protesters into a high school. The police fired tear gas into the school and shot demonstrators with rubber-tipped bullets. Two teenagers lost eyes, and numerous others were hurt. One of them was the city’s then-mayor, Sheikh Raed Salah. If his name rings a bell, it should, because today he can reasonably be characterized as the most-feared Arab leader in Israel, at least among many Israeli Jews. Sheikh Raed has another connection to our story, but we’ll get to that later.

Ask people in Israel today what they know of Umm al-Fahm. A few might have heard of or even visited the Gallery, but most who can identify it at all will tell you that it’s a hotbed of Islamic extremism; that, for example, the two terrorists who shot and killed two members of the Border Police in a March 27 shooting attack in Hadera this year, were both from Umm al-Fahm. People are also aware of the extent to which Umm al-Fahm has been hit by violent crime in recent years, as have many Arab towns and cities in the country, a phenomenon that has complex and intertwined roots, and that the state has only belatedly begun to address, having understood that the crime wave threatens Israeli society in general and not just its Palestinian citizens.

So it was in 1999 as well. Even Jews who might in quieter days be interested in visiting Umm al-Fahm were afraid to step foot there. At the gallery, they understood that they needed to reassure the people who wanted to rub shoulders with Yoko Ono that it was safe to come. So, when visitors arrived at the turnoff from Highway 65 on that sunny, chilly Saturday morning in November 1999, they were directed to pull into an improvised parking on the side of the road. From there, they were shuttled in vans up the steep side of Mt. Iskander to the gallery, where the opening of the exhibition took place in the presence of several hundred guests. (It wasn’t just visitors’ fears that made that the shuttle service a good call: Like many other Arab cities in the country, all of which predate the state’s founding, Umm al-Fahm’s streets are often narrow and unmarked, and having hundreds of private vehicles trying to negotiate their way up the hill to the gallery could have had disastrous results.) For many it was the first time they had visited Umm al-Fahm; in fact, for many it was their first time in any Arab town, so high are the social barriers that discourage mixing between Palestinian and Jewish citizens.

• • •

My experience that day in Umm al-Fahm was a revelation. Sure, I still remember the ceremony inside the small gallery, as Shimon Peres, at the time the minister for regional cooperation, pushed members of the crowd, me included, aside so that he would be visible to the cameras as he made his way to the front to officially welcome the artist. And I remember my surprise when I saw that Sheikh Raed was another of the dignitaries there to greet Ono and the visitors. I hadn’t even known he was the mayor, and only recognized him as the founder of the separatist “northern branch” of Israel’s Islamic Movement. I had never imagined that an Israeli city could have an Islamist mayor.

But the real astonishment I felt was caused by the gallery itself. It had been founded only three years earlier, but it was obvious that it was far more than an exhibition space. The other shows on display revealed a sophisticated curatorial hand at work. The gallery’s director, Said Abu Shakra, was gracious in his remarks, and told the audience, who included Jews and Arabs, many of the latter residents of this conservative, working-class town, of his plan to turn the institution into a full-blown museum of Palestinian culture.

No less impressive was the efficiency with which the event proceeded. After the welcoming remarks, guests were invited outside to a large tent, where a generous buffet of Arab dishes was served, without the usual long lines one might have expected, although there were hundreds of guests. Following the official event, those who were interested split up into small groups, each of which was invited to visit in the residence of a different local family that had volunteered to give the outsiders a dose of Arab home hospitality.

It soon became clear that this was as rare and valuable an opportunity for the hosts as it was for us outsiders. The extended family of the couple that received my group were crowded into their living room, and each one was introduced to the visitors. They were eager to tell us about their lives. In particular, they were anxious to talk about the violence they had experienced at the hands of the police earlier that fall. Someone had gone to the trouble of blowing up color photographs, each the size of a small poster, depicting the injuries suffered by their neighbors, and one of their sons, when they were chased into the high school where they had attempted to take refuge.

The visit, which of course also included the traditional cups of tea, Arab pastries and cut-up fruit, went on for well over an hour, and it surely left a number of the guests shaken. We thought we were coming to the opening of an art show, and suddenly, those of us who had chosen to remain found ourselves being confronted by first-hand descriptions of the fraught complexity of relations between Israel and its Arab population.

Remembering that today, I can understand just how audacious a decision it was to offer the home visits, and how easily things could have turned sour. For me, the day served as something of an epiphany, and I resolved to return in the near future by myself to learn more about the Umm al-Fahm Gallery of Art and its ambitious founder, Said Abu Shakra and his brother Farid.

I have been writing about the Abu Shakras, their gallery, and Umm al-Fahm -- and more generally about Israel’s Palestinian citizens -- ever since.

• • •

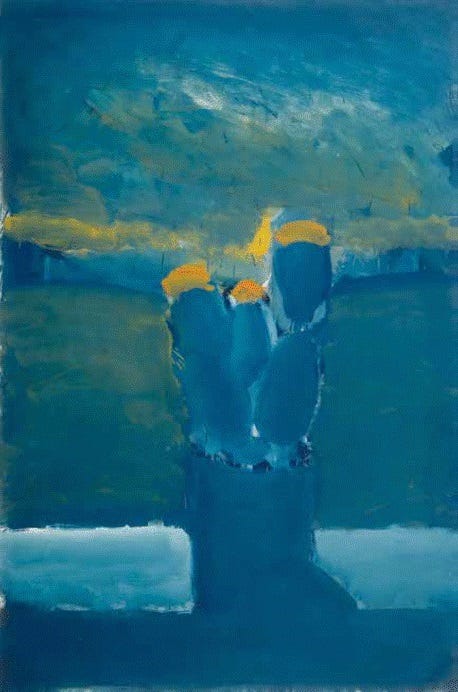

On November 11, 2022, the Ein Harod Mishkan Museum of Art will open a retrospective show of art by five members of the Abu Shakra family, and curated by Galia Bar Or and Housni Alkhateeb Shehada. In addition to Said and Farid, they include their late brother Walid, and also their cousins Asim (also deceased) and Karim Abu Shakra. Each of the five has made an important contribution to Israeli art and to Palestinian culture in Israel, but for me, they represent something else as well, something harder to define but no less meaningful.

The five Abu Shakras belong to the first generations of Israeli Arabs following the Nakba. That’s the Arabic word for “catastrophe,” and is how Palestinian Arabs refer to the events surrounding the founding of the State of Israel, which for them led to the departure of some 700,000 of their brethren from the country. Only some 150,000 remained, and it is they and mainly their descendants who today constitute more than 20 percent of the country’s citizens.

There are some Israelis who still hope to see those 1.5 million Arabs driven out of the state, or at least disenfranchised. Some of them will be senior ministers in the government that looks to be formed following the November 1 election. The type of scenarios they casually allude to would be unthinkable if realized – on practical and moral levels, and by any common understanding of international law. And after the worst of it, I would submit, the survivors on both sides will have no choice but to acknowledge that neither is going away, and that they are destined to share this land that they both love so deeply. This week, to be sure, that moment of understanding appears far away, but it will come someday. Surely we can find a way to reach reconciliation without having to pass through an apocalypse.

The mounting of a major exhibition of art by Palestinian Arabs at a museum that is part of a Jewish kibbutz is, therefore, an important event – it presents a window for visitors into the conceptual world of their Arab neighbors, who, just as the Jews, experienced a national trauma in the preceding century. The paintings are not political, certainly not didactically so, but they cannot help but address the experience of what it means to be a Palestinian citizen in the State of Israel. Learning about that doesn’t need to be an existential threat for Israelis. On the contrary, refusing to acknowledge that “narrative” must ultimately constitute an existential threat.

If you enjoy this post, please subscribe, and please recommend to others you think might be interested. (And of course, feel free to unsubscribe if it’s not for you.) That way you will receive future posts in your email.

David - Thank you! As a member of the New York-based board of The American Friends of the Umm el-Fahem Museum of Contemporary Art (what we hope will be the future of the Umm el-Fahem Gallery), I am very appreciative of your presentation of the Gallery. We hope that visitors to the Ein Harod Museum's exhibit of Said's and the other Abu Shakra family artists's work will be blown away by the talent displayed and the significance implied. And we also hope visits to the museum will be followed by visits to the Umm el-Fahem Gallery by those who have not yet been there. I look forward to following your blog.

Fascinating. So much I didn't know. Learned a lot from this and looking forward to following you...