'There is no replacement for the truth'

I try not to think about Yitzhak Rabin -- too painful. But the 30th anniversary of his killing was an opportunity to recall certain key aspects of his greatness, with the help of Effie Shoham

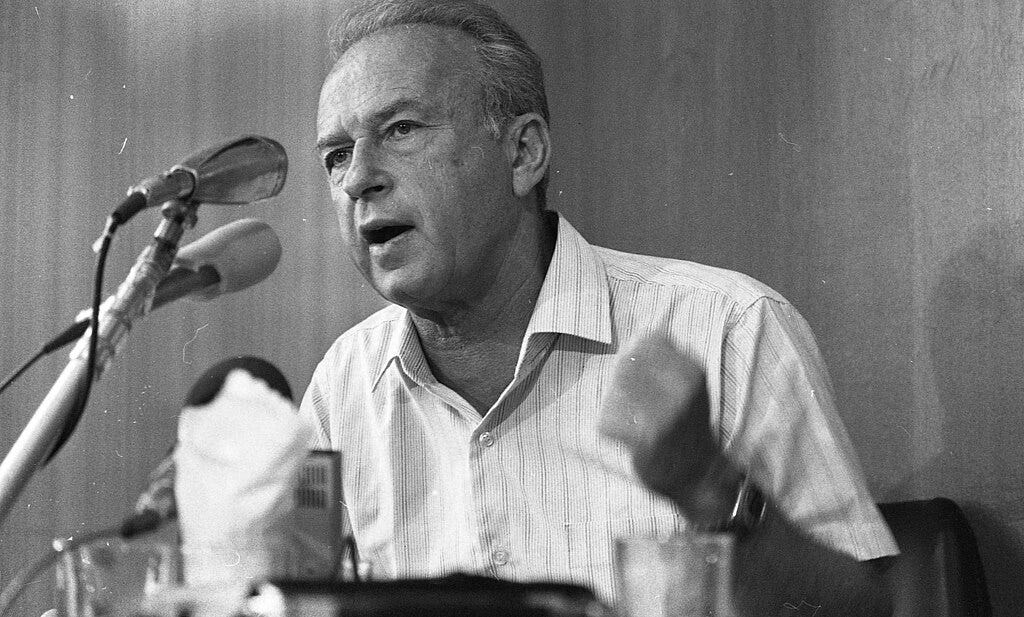

This year marks 30 years since the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, who was killed as he departed a mass peace rally at Tel Aviv’s Malkhei Yisrael Square, later renamed for him. This past Monday, November 4, 2025, an ad hoc coalition of groups in Jerusalem, with support from City Hall, held a memorial event at the Smadar cinema.

With one Netanyahu government or another in power for nearly all of the past 16 years, Rabin, whose adult life history corresponded heroically with most of the state’s first five decades, has been largely relegated to anonymity. Certainly, much of the younger Jewish generations here have been indoctrinated to see him as akin to a traitor, for his readiness to sign a peace accord with Yasser Arafat and his Palestine Liberation Organization, and to begin the difficult process of attempting to enter a process that was intended to end in Palestinian autonomy, if not statehood, in the areas occupied by Israel during the Six-Day War, in 1967.

Recalling Yitzhak Rabin today, I realize that I have suppressed many of my memories of him, and of the period surrounding his murder by an extremist Jew, a law student no less, who saw it as his mission to stop the peace process, even at the cost of his own life. (The murderer was captured alive, and is now serving a life sentence, although it is easy to imagine a government much like the current one arranging for a pardon in the future.) The political and social developments that have characterized the past 30 years have been horrifying, to put it bluntly, and thinking about what might have been is more than I take on.

(I write the above well aware of the precarious state that the “peace process” was in in November 1995, and I know that the high hopes I had at the time may well have been naïve. But democracies can’t survive when political violence is seen as a way of solving conflicts, and every step taken by Israel since then has brought us further away from the ideals – themselves far from perfect -- laid out in our Declaration of Independence, and from anything resembling reconciliation with the Palestinians who share our land with us.)

The event at the Smadar two nights ago brought back a flood of memories of Rabin – of his honesty and his courage, of the political vision he had even as a young officer before the founding of the state, and of a certain shy social awkwardness he possessed that made him all the more human and credible. So different is our political culture today that it should be understandable why I find it hard to think about Rabin.

One of the most moving parts of the evening for me was a brief speech given by Ephraim (Effie) Shoham, a professor of medieval Jewish history at Ben-Gurion University. Shoham’s son Staff Sgt. Yuval Shoham fell during his service in Gaza on December 30, 2024. Effie was active in Jerusalem’s protest movement from its beginnings in January 2023, when the government initiated its ongoing effort to emasculate the legal system, and the death of his son, if anything, accelerated his involvement in the weekly demonstrations. (I wrote about him after hearing him speak at a Tisha B’av event around the corner from the Prime Minister’s Residence this past August.) He combines erudition, eloquence and the restrained dignity of a father still mourning for his son.

I asked Shoham for permission to translate and post his remarks from the Rabin event, in which he found, as people like him seem to have the magical ability to do, a meaningful way to connect the anniversary with the previous Shabbat’s Torah portion, with an implied message about our current leadership that he had no need to spell out.

I am publishing that translation it here almost in full, and hope you find it as beautiful as I did. (Shomrim al Habayit Hameshutaf also posted a video of the original Hebrew speech, which you can view here.

Prof. Shoham’s remarks at the Rabin anniversary evening:

This past Shabbat, we read the Torah portion of Lech Lecha (Gen. 12:1-17:27).

One of the central events that takes place in the parsha is the story of the kidnapping of Lot, the nephew of Abram (as he was then called), during the course of the war of the four kings against the five kings. This was preceded by a family conflict, during whose course Abram’s family decided to split up. This led to a painful parting between Abram the Hebrew and his adoptive son Lot, son of his brother, who had accompanied him the entire way from Ur of the Chaldeans to Elon Moreh. Abram remained in Canaan, while Lot, together with his flock and his possessions, migrated to the plains of Sodom, which was still “like the garden of the Lord, like the land of Egypt.”

Now, however, despite the distance, the conflict, and the separation, and in spite of the ideological gap and other differences – at the moment of truth, when a family member falls into captivity, you don’t begin to settle accounts.

“When Abram heard that his kinsman’s [household] had been taken captive, he mustered his retainers, born into his household, numbering three hundred and eighteen, and went in pursuit as far as Dan”(Gen. 14:14). Though Abram is already in his mid-80s, he displays a sense of responsibility and mutual obligation, and he hurries to defend and save Lot. Although Abram’s offensive capability is limited, and he is no real position to take on the armies of the four kings, commanded by Chedorlaomer, he takes off in pursuit of those forces, which are laden with booty and their captives, from Sodom to Dan, in the far north. He attacks their camp, frees Lot, and then continues with his force after the escaping troops all the way to Damascus, before returning to his home in Elon Moreh.

What characterizes Abram in this episode is the way he takes responsibility and demonstrates his sense of mutual commitment.

I was a young man when I experienced the murder of our country’s prime minister (also defense minister), and for me, the pain was palpable. In the year preceding the assassination, when the hopes and chances for peace multiplied, but so did the dangers, our first son was born. We decided to name him Shahar, meaning “dawn,” because he was born on the day that the peace treaty between Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. The name gave expression to our yearning for the new era on whose brink we hoped and prayed we were on.

It’s not my intention to speak about the great promise or the obvious difficulties that accompanied the peace process into which Yitzhak Rabin entered. I want, rather, to raise a single point that is connected to his raw personal style, something that connects him to Abraham – that sense of mutual responsibility and obligation.

Rabin was no saint, and he certainly made his mistakes, but for me, he remains a symbol of those qualities.

Rabin grew up in a Tel Aviv that was modest and working-class, with two hard-working parents. His mother, Rosa Cohen (known as “Red Rosa,” as we learn in the excellent new biography of her written by my friend Nurit Cohen), was totally immersed in her work at Haganah headquarters, while his father, Nehemia, worked in the telephone service of the British mandatory government. Hence, from a young age, Yitzhak had to watch after his younger sister, Rachel. That sense of obligation remained with him when he went on himelf to serve in the Haganah, and later in the Palmach commando corps.

Throughout the entire course of his military service, Rabin was identified with his sense of commitment, even when it led to conflicts with his senior officers. During the War of Independence, for example, during the battles on the road to Jerusalem, and following the success of Operation Nachshon, a serious dispute erupted between the part of the army led by Yigal Allon and Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, regarding the need to conquer the fort at Latrun, which Ben-Gurion was insisting upon.

It was Rabin who decided to travel on behalf of Yigal Allon to Ben-Gurion, so as to convince him to call off additional attacks on Latrun, after attempts that had already concluded with no gains and dozens of casualties.

All through both his military and political careers, Rabin demonstrated a sense of responsibility. Sometimes he was rewarded with success, as was the case with Operation Entebbe in 1976, when, as prime minister, he gambled on the IDF’s ability to reach Uganda and free the passengers of the hijacked Air France plane. But there were also bitter failures, as in the case of the attempt to free the soldier Nachshon Wachsman, captured by Hamas, in 1994, during Rabin’s second term as premier. Both Wachsman and Capt. Nir Poraz, of the Sayeret Matkal commando force, died during that operation. Thereupon, Rabin appeared before the cameras, and declared that he took full responsibility for the event and its results.

Rabin’s tendency was to look reality straight in the eye, always with the goal of improvement. He preferred that to ignoring failure, devising a spin to explain it away, writing a alternate narrative, or otherwise attempting to shake off responsibility, even if it made him look bad.

I will complete my remarks with some of Rabin’s own words, and then with a short tale from the past year, one that left me with a feeling of hope, despite the great pain and regret that has enveloped me and my family in the 10 months since our son Yuval fell in Gaza.

In the famous speech that Rabin delivered at the concluding ceremony at the IDF Command and Staff College in 1992, the year he assumed the prime ministership a second time, he spoke out angrily in condemnation of the attitude of “yihiyeh beseder” (“it will be okay”) and “don’t worry,” not to mention cover-up. Less well-known today are several sentences that he spoke toward the end of the speech. After referring to the need to adhere to orders and rules and, he added these words:

“… [I]n the framework of orders and rules, there is also a need to exercise common sense in the face of changing circumstances. A good commander is one who sees things as they are, who evaluates the situation properly and finds the simplest and best solution. We require him to be a human being. It’s easy to become drunk on authority and power. Our boys and girls, your soldiers, are like clay in the hands of the creator – and you are the creators. Your obligation as commanders is to extract the best from your soldiers, but also to cover them up at night, to meet them at the end of a demanding hike with sandwiches and a drink, to be with them during the difficult moments, to be both a father and a friend, as needed.

“We expect you to speak the truth. There is no replacement for the truth, even when it is bitter…”

When Yuval fell, in Jabalya [in Gaza], his unit continued to fight, and his commander, Lt. Col. Nati, was unable to get to his funeral or to the beginning of the shiva. But he called us.

He asked for the whole family to gather around the telephone, which he asked me to set on speaker mode.

“I request your forgiveness, members of the Shoham family. I made a commitment to get Yuval back to you safely from the battlefield, and I failed in this mission. I accept full responsibility for what happened. The failure is mine and mine alone.”

I thought to myself that, although Yitzhak Rabin has been gone for three decades, his spirit continues to be present in many places. I was struck by the ability of an officer in his 30s, who was almost certainly still a toddler when Rabin was killed, to truly understand what those older than him never knew or chose to forget.

That brief and difficult conversation planted in me the hope that Rabin’s legacy, in this realm as well as in others, remains engraved in the hearts, souls and spirits of many -- in the army in which he grew up, in the State of Israel which he so loved and which he led, and in the people of Israel, for whom he dedicated his life. Let his memory be a blessing.

(The preceding are the remarks delivered by Prof. Ephraim Shoham at a memorial event for Yitzhak Rabin in Jerusalem on November 3, 2025. Translation by DBG.)