Their 'three lines of history'

An April Holocaust tour of Poland gives rise to thoughts about the meaning of heroism, mutual responsibility and the value of choosing how one will die, when faced with the inevitable

Our first day in Krakow was deceptively calm, even pleasant, although we all knew what was coming the next day: Auschwitz. In the meantime, however, there we were, standing in the late afternoon sun on the sidewalk outside 13 Jozefinske Street, listening to our guide tell us the story of the Akiba youth movement, which had, for a few months in 1942 used a ground-floor apartment in the building as a communal living space. There’s no plaque at the site, and nothing to visit per se, but the story we heard kept our group transfixed for the better part of an hour, even as the air took on an increasing chill.

Akiba was a Polish-Zionist youth group founded in 1924. Much of what is known about its activity during the German occupation of Krakow, comes from the remarkable memoir “Justyna’s Narrative,” written by Gusta Dawidson Draenger, one of the youth movement’s leaders. Imprisoned by the Nazis in Krakow, Justyna (her nom de guerre) was convinced that neither she nor any of her comrades in the underground would survive the war, and felt compelled to record for her fellow Jews in the Land of Israel “a faithful picture of the last, most daring rebellion of our lives.”

That rebellion included taking up arms against the occupiers, but in a more fundamental way, it also can be understood as the self-transformation of a group that was principally religious, cultural and social in its activity, into an autonomous and mutually supportive community whose members gave meaning to their lives in the way they chose to go to their deaths.

* * *

We had arrived in Krakow late the night before, a group of 17 veterans of the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement from Israel, ranging in age roughly from 30 to 75. This was the first time that the movement had organized a Poland journey for adults similar to the tours it has been running for young people for years. Our six-day itinerary was to include visits to Krakow, Lublin and Warsaw, all of which had sizeable numbers of Jews prior to the Nazi occupation of the country, and to a handful of concentration and death camps where millions of them met their deaths.

A “Holocaust tour,” to be sure, but one that was designed in such a way that we got a brief glimpse too of the rich 700-year history of Jewish Poland that didn’t treat that history as if it were merely the prelude to the inevitable act of destruction that brought it to an abrupt end in the mid-20th century.

That first day, for example, had begun with a brief visit to grounds of Krakow’s Wawel castle, a vast hilltop complex that embodies the national and religious history of the Polish people, its earliest structures having been built more than a millennium ago. From there to Kazimierz, the old Jewish quarter of Krakow, whose first Jews arrived in the 13th century, at the invitation of the Polish monarch, is a walk of only a few minutes. And it is from Kazimierz, with its historic synagogues and cemeteries, that they were expelled to the far side of the Vistula river by the German occupiers. In that sense, we were following in the footsteps of the city’s last Jews, when they were forced to take up residence in the newly established ghetto in the workers’ quarter of Podgorze.

The creation of the ghetto was part of the plan of German governor-general Hans Frank, who shortly after Krakow was designated capital of the part of Poland that was not incorporated into the Third Reich, announced his ambition to make it the “racially cleanest” city in the realm. Thus began the process of deporting to the countryside all but 15,000 of the approximately 70,000 Jews then living there. They were gradually subjected to increasingly harsh restrictions, until, by March 1941, those who remained in Krakow were forced into the ghetto.

[photo of ghetto wall: "C:\Users\USER\Documents\Substack and other pubs\blog\2025\yom hashoah\yom hashoah images\960px-Kraków_Ghetto_wall_62_Limanowskiego_Street By Adrian Grycuk.jpg"]

It would not be hyperbole, then, to say that the Krakow Ghetto was created solely in order to be destroyed, and although there were several workshops in the ghetto that employed Jewish prisoners in forced labor – most famously Oskar Schindler’s enamelware plant – it’s clear that the ghetto was mainly intended as a waystation to hold Jews from Krakow and environs until they were dispatched to be murdered. It existed roughly between March 1941 and March 1943, when its final residents were deported to Auschwitz, and the ghetto was considered liquidated.

Akiba was the largest Zionist youth movement in pre-war Poland, and one of the founding members of the Hehalutz Halohem (“the pioneering fighter”) – the Jewish resistance movement that sprung up in Krakow, under the direction of Akiba leader Aharon “Dolek” Liebeskind. He was assisted by Szymon “Szymek” Draenger and his wife, Gusta Dawidson -- Justyna.

Gusta was born in 1917 into a family of Gur Hasidim in the city. Akiba was not a “revolutionary” movement -- unlike, for example, Hashomer Hatzair, which initially insisted on having its own, more militant underground, called Iskra. From what is known, Gusta remained close to her family even as she became deeply involved with the Zionist and religiously moderate youth group.

In an Israel Radio broadcast from 1982, Hela Schiffer Rufeisen, a surviving member of Akiba and of the underground, had grown up in the same Krakow neighborhood as Gusta, and recalled her as “always outstanding, always most active, full of life.” Speaking on the same program, Yehuda Wasserman Maimon recalled how Gusta possessed “a poetic soul,” but was at the same time “was a fighter.” And Genia Meltzer, who was a cellmate of Justyna’s in her final incarceration, in the Helzlaw women’s prison, recounted how Gusta “prevented us from succumbing. Although she firmly believed that we could expect nothing but an early and violent death... she made us wash and brush our hair every day, as long as the water lasted, and she made certain that the table was cleaned every day.”

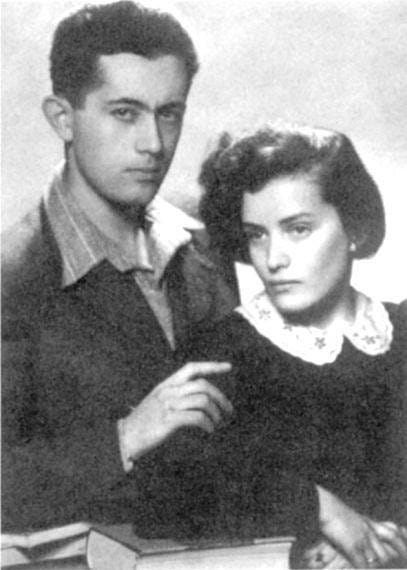

Most of the leaders of Akiba had emigrated to Palestine after the German occupation in 1939. Gusta and Szymek and Dolek were among those who remained behind in Krakow. The first two were married in 1940 and were fiercely devoted to one another. Together, they were responsible for writing and editing Akiba’s various publications, continuing this work even while living “underground” in the forest.

During the Aktion of spring 1942, the parents of their Akiba comrade Shimon Lustigman were deported, and their two-room apartment on Josefinske Street was left empty. Shimon put it at the disposal of his comrades. It became a beehive of activity, where members ate and slept, and gathered each Friday evening to welcome the Sabbath. In her diary, Justyna described how it also was turned into a “liquidation office,” where other members who had lost their families could bring “everything that was left in their home: linens, clothing, shoes, valuables – in short, everything that could be shared or converted into money that could be used by the group… Everyone said what he was in need of, and received something appropriate. The property of individuals became that of the group….

“In place of the lost family space, came another shared space, which sprouted not out of blood ties, but out of spiritual ones” (My rough translation of the Hebrew edition of “Yomana Shel Justyna”).

By late November 1942, however, an understanding had taken hold that it was no longer safe for the group’s members to be seen together (those involved in the armed underground were already living in separate quarters), and that the more time they could spend outside the ghetto, the better it would be for those qho remained. Thus, on November 20, Justyna wrote, “We welcomed the Sabbath Queen together for the last time.” Dolek, calling their gathering the “Last Supper,” explained to the group that, “We are known, there is too much talk about us. This week we will begin to liquidate this place, No. 13, that has become so beloved by us. …”

To be clear, Dolek did not attempt to placate members with false hopes of victory. In the same short speech, he told them explicitly, “We are marching toward death, remember this. Whoever desires life should not pursue it here.” But at the same time, he expressed his belief that “we cannot allow ourselves to regret anything. This is what has to be!... We are fighting for our three lines of history. These three lines will redeem our honor and the honor of the Jews.”

In the weeks that followed, the Halutz Halohem group carried out several actions against the Germans, the most dramatic of them on December 22, 1942, when they carried out a coordinated grenade attack on Café Cyganeria, in central Krakow, where officers of the occupiers were known to congregate. Eleven Germans were killed, and another 13 were wounded. But the Germans responded with a massive manhunt and killed many of the rebels, including Dolek. Others were arrested, one of them being Szymek, who was spotted in Krakow in early January 1943.

Szymek and Justyna had agreed between them that if one of them was arrested, the other would turn him- or herself in to the Germans. Justyna had done just that in 1939, when Szymek was arrested for his work as editor of the Akiba newspaper, and she entered the local Gestapo headquarters and surrendered. She and Draenger were later released after their families and hanichim (followers) from Akiba assembled a bribe for their captors.

Now, in early 1943, Justyna again turned herself in. She was imprisoned in Helzlaw women’s prison, across the street from the Montelupich prison, where Szymek was held. That is when she began writing her diary, incredibly, on individual sheets of toilet paper that were smuggled into her cell.

She wrote in the name of herself and other members of the resistance, addressing their comrades in Palestine in “the last greetings of young fighters as we fall for our highest and most sacred goal.... We pray that these few memoirs, written on scattered pages, will give you a faithful picture of the last, most daring rebellion of our lives.... Whatever we do we're doomed, but we can still save our souls. The least we can do now is leave a legacy of human dignity that will be honored by someone, some day." (This translation from the English-language edition of “Justina’s Narrative,” as cited in the biographical entry on Dawidson in the Jewish Women’s Archive.)

Several other women in the cell, including Genia Meltzer, survived the war, and described the process by which the diary was written. According to Yael Peled’s article in the Jewish Women’s Archive, there were times when Gusta’s hands “were in so much pain from her tortures that she could not write, [and] she would dictate her diary to her comrades. In order to keep her words from being heard outside, some of the young women would sing while others watched out for the guard.”

On April 29, 1943, while being transported with other women prisoners to be executed at Plaszow prison camp, Gusta participated in, and survived, an escape. She made her way to the forest outside Krakow, and was reunited with Szymon, who also had escaped. For the next six months, they held out, living in a bunker prepared by the Jewish underground, and together published a weekly newspaper called Hehalutz Halohem. Each Friday, they arranged to distribute 250 copies of their 10-page bulletin among the remaining Jewish ghettos and in the forests where the last holdouts could be found.

By November, the two decided to attempt to cross into the relative safety of Hungary. Followed by the Germans, Szymek was arrested as he met the person who was supposed to smuggle him across the border. Informed of his capture, Gusta again turned herself in. It is assumed that the two were promptly executed by the Germans, although the details of their death remain unknown.

By then, the Krakow Ghetto had been disbanded, its 10,000 remaining Jews either killed on the spot, sent to hard labor at Plaszow, or deported to Auschwitz to be murdered. The members of the ghetto’s Judenrat and Jewish police, and their families, were spared a bit longer, until December 14, 1943.

According to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, more than 4,000 Jews returned to Krakow after World War II. By early 1946, their number had swelled to nearly 10,000, as refugees returned to the city from the Soviet Union. They were not warmly welcomed in the liberated city, but in fact faced pogroms, so that most ended up emigrating from Poland.

The story of the piecemeal survival of “Justyna’s Narrative” is itself a drama with many chapters, stretching over several decades. Eventually, what are believed to be the entire contents of the book were assembled and published by the Ghetto Fighters Museum. When I spoke in April with Simcha Stein, a historian and educator who for 16 years directed the museum, at Kibbutz Lohamei Hageta’ot, he told me that, “What we have is apparently complete… we have the entire book, and its many chapters,” which is more than 100 pages in its published form.

Gusta Dawidson Draenger is without doubt an inspiring and heroic figure. She was a youth leader, an underground activist whose job required her to move from city to city, acting as a coordinator for fighters. That work overlapped with the expert forging of documents that was the specialty of her husband, Szymon Draenger. Comrades testified that her devotion to Szymek was the source of some pain to Gusta, as his single-minded dedication to the military mission made him less than fully attentive to her.

Gusta’s writing sings, even in translation. In one segment of her diary, she describes a period when she and some of her comrades were on an Akiba training farm (intended to prepare movement members for Aliyah to the Land of Israel). This was 1942, and the German occupation was already several years old, but the final destruction of Krakow Jewry had not yet begun. Here is what Justyna, writing from her cell the following year, recalled, as translated by Roslyn Hirsch:

“The sun was sinking behind the forest, which extended... into the distance like a dark stain till it fused with the Blue Mountains in the far-off horizon. The stillness hovering luxuriantly above the orchard spread itself across the golden fields, lay down indolently in the dense pastures, circled the mansion, and expired in the boundless forest. Summer was at its peak. No one had returned yet from the fields. As far as the eye could see, not a soul disturbed nature's stillness with even the slightest movement. All creation seemed suspended in the heat of the summer day. In the profound silence, it was easy to forget that war was raging and blood being spilled, that violence, evil, brutality, lawlessness, human injury and pain existed on this earth."