The best thing right now is to keep silent

What does it feel like to be a Palestinian citizen of Israel when Israel is at war with Palestinians?

Two weeks after the October 7 attacks that initiated Hamas’s current war with Israel, Said Abu Shakra was still staying away from Facebook. That was unusual, as Said is always on Facebook - sometimes posting snapshots of visitors or announcements from the Umm Al-Fahm Gallery of Art, which he founded and directs, sometime sharing breathtaking drone videos shot by his son Muhamad over snow-draped Alpine landscapes, or more recently, photos of the grandchildren that have begun to enter his life.

I called him. Normally cheerful and always busy, he was very down, and had the time to talk about it. The war was brutal, and no end was in sight. A week later, that is still the case, and there is even a fear that the hostilities will spread to additional fronts. Forty Israeli residents remain missing or unidentified, and only a handful of the 240 in Hamas captivity have been freed. The deaths and destruction being suffered by Palestinians in Gaza are no less horrific, for anyone willing to consider them.

Abu Shakra is not someone who discourages easily, and in fact is at his most creative when faced with a difficult challenge. But terrible darkness had descended on our contested land, and at the moment, he could think of no better alternative to keeping quiet. At the best of times, his identities as both a Palestinian and an Israeli citizen are in conflict of some kind, but now, Said understood that there was nothing he could say that would not cause offense on one side or the other.

In earlier entries appearing here, I have described the family Said grew up in, in which an illiterate mother, who raised seven children largely on her own during the precarious early decades of Israeli statehood, encouraged each of those children to get an education and then to pursue the career of their choice. As a result, three of her sons became world-class artists – something that among middle-class parents in the West would likely be a cause anxiety and concern, but in Arab society was almost unheard of.

In the case of Said, who is today 67, he studied art in Tel Aviv while working as a youth officer in the Israel Police. A realization that the country’s Arab community did not have a single art gallery or museum of its own, led Said, together with his younger artist brother, Farid Abu Shakra, to set a gallery up in Umm al-Fahm, the urban center of Arab communities that straddle Highway 65 in the Wadi Ara region of the country, southeast of Haifa. That was in 1996, and 37 years later, the Umm al-Fahm Gallery of Art is not only recognized as one of Israel’s leading venues for contemporary art by artists both Arab and Jewish, as well as non-Israelis, but also serves as a rare meeting place for people from both groups, as well as an important cultural institution for the residents of its host city, the conservative, working-class Muslim population of Umm al-Fahm.

Finally, a year ago, it seemed as if the state was going to acknowledge the important role played the gallery in Israeli culture by recognizing it as the country’s first Arab museum. This would not be equivalent to a financial windfall, but it would provide the funding and professional support that would allow the gallery to bring its facility and staff up to museum standards.

That was before the country’s most right-wing government ever won an election, before a whole range of promises made to the Arab population by the previous government were frozen in place, and of course before a full-scale war broke out. The plan to establish a museum has been moribund for nearly a year, and it’s been months since the government stopped delivering the funding that the roughly 150 cultural institutions serving the Arab population depend on like oxygen simply to operate.

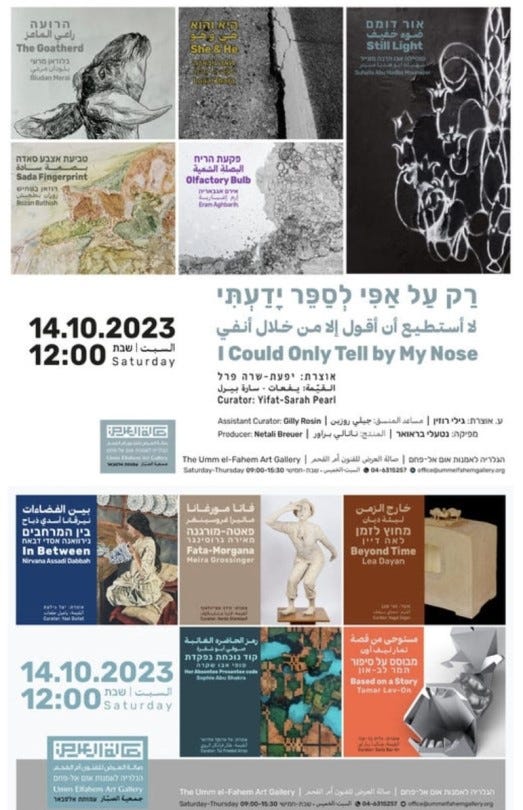

Needless to say, the gallery has been closed since October 7, and the opening of 10 new mini-exhibitions that had been scheduled for October 14 was postponed indefinitely. Said’s fundraising trip to New York, which had been planned for this month, is off. And a show of his his own artwork that was slated for the gallery at Mishkenot Sha’ananim, in Jerusalem, has been cancelled. If a year ago, Said and his colleagues believed the gallery was on the cusp of a new era, today they recognize that it is very much in survival mode. For Arab citizens of Israel, that is not an unfamiliar place to be.

The only piece of mildly encouraging news he had to share was that he intended to open the gallery to the public that coming Shabbat, and would post an invitation on Facebook. Facebook!

When I arrived at the gallery a few days later, however, I didn’t see any other visitors.

The gallery is situated in an industrial-style building two-thirds of the way up Mt. Iskandar, across which Umm al-Fahm sprawls chaotically. If you are fortunate enough to squeeze out a parking spot near the gallery on Haifa St., you will either need to hike up the steep hill to its door, or brace your knees for a sharp descent to its entrance. On the ground floor of building are a few small interconnecting gallery spaces, and beyond them, a room holding a partial re-creation of the London print workshop of Walid Abu Shakra, the oldest of the three Abu Shakra brother-artists. Walid died in 2019, and a short time later, the gallery added a dedication in his memory to the full name of the gallery.

When I stepped inside from the street, I was greeted warmly by Netali Breuer, the gallery’s project director, someone who exudes a quiet competence, and who I like to imagine knows a lot more than she’s saying. Netali and a colleague, Ahmad Mahajna, were painstakingly affixing to the wall the name and credits – in Arabic, Hebrew, and English – of an exhibition titled “I Could Only Tell by My Nose.” It’s one of the 10 shows that was supposed to have opened to the public on October 14, and although it still doesn’t have a new date, Netali and her colleagues are clearly ready to get back to work.

Netali told me I would find Said on the second floor, where the principal exhibition spaces and its offices are, but there too, I encountered a series of galleries empty of visitors -- all dressed up with no place to go. Aside from Salma at the reception desk, I saw no one until I glanced into Said’s office, and saw him seated there with a half-dozen hijab-wearing women, members of the gallery’s staff. Said had convened them to discuss the gallery’s near future.

Clearly, the plan to reopen, if only for a day, had been dropped, and I hadn’t gotten the memo. My gingerly attempts to find out why were unsuccessful. But after the staff meeting concluded and I got to sit with Said, I got a sense of just how bad things were.

Other than a walk each evening with his wife, “this is the first time I have left my house” in three weeks, Said told me.

During Israel’s earlier campaigns in Gaza, which have taken place every few years since the takeover by Hamas in 2007, Arab citizens would often hold demonstrations protesting Israeli bombing raids over the Strip and the number of non-combatant casualties. This hardly endeared them to the Jewish population, but the marches took place in their own towns, and usually received minimal attention from the media. This time, it’s different.

The magnitude and the nature of the October 7 cross-border attacks were way beyond any previous terror attack suffered by Israel, and changed the public conversation entirely. Today, it is the rare Israeli Jew who is willing to hear even a full-throated condemnation of Hamas if it is followed by the word “but.” Nor are many Israelis ready to hear any expression of sympathy for Gaza residents who have been hurt or displaced by Israel’s military response.

On October 22, a patronizing police commissioner, Koby Shabtai, offered praise to the country’s 2 million Arab citizens for their “exemplary” behavior over the preceding fortnight, noting that there had been “zero incidents” requiring action by the police during that period. Of course, he himself may have contributed to the tense quiet with his Arabic-language clip posted on all the social media five days earlier, when he announced to anyone who was considering expressing sympathy for the people of Gaza that, “Whoever wants to be a citizen in the State of Israel is welcome [“ahlan wasahlan,” in Arabic]; anyone who wants to identify with Gaza is invited -- I will put him on the buses that are taking people there…” Note that Shabtai spoke about expressing identification “with Gaza,” not “with Hamas.”

“As soon as the war broke out,” recalled Said during our phone conversation, “I wrote to my children: Don’t any of you do anything - not on Instagram, not on Facebook, nowhere else. You don’t write anything online, not even a ‘like.’ This is not the time to talk…. because anything at all that you write, you will be held responsible for it.”

Sure enough, within a week, the State Prosecutor’s office announced that it was keeping a close eye on Arab citizens’ activity on social media, and already was investigating up to 100 people on suspicion of supporting terror or incitement, a crime that could lead to up to 10 years in prison.

In his oped piece published this week in The New York Times, Israeli human-rights attorney Michael Sfard noted that, “as of Oct. 25, over 126 criminal investigations have been opened and 110 arrests have been made after individual statements made in public, on social media or in closed groups regarding the events of Oct. 7 and the ongoing war in Gaza.” Sfard explained that this frenetic legal activity is being assisted in part by the surveillance efforts of “a task force established a few months ago to monitor so-called Palestinian incitement to terrorism on the internet.”

One of the most publicized cases of someone being punished for his online posts was a cardiac surgeon, Dr. Abed Samara, who was fired from his job as director of the cardiac intensive care unit at Hasharon Hospital, in Petah Tikva, after someone dredged up a Facebook profile of his that included a green Islamic flag on which is inscribed the Shahada, the Muslim declaration of faith (“There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is his messenger”). Below that was a picture of a dove carrying an olive leaf

In its ignorance, and without going to the trouble of giving Samara a hearing, the hospital immediately removed him from his position, and referred his case to the police. Similarly, the health minister released a statement on Twitter/X claiming that Dr. Samara had published a “Hamas flag and words of support for the terror organization that slaughtered hundreds of Jews in cold blood.” A simple check by either the hospital or the minister would have revealed that neither claim was correct, and also that the statement of supposed support for the October 7 massacre had been published in 2022. To date, however, Hasharon Hospital has not reversed its decision on Samara’s employment.

So, yes, Israeli Arabs have been very quiet since October 7. I refer readers as well to a chilling article in my own newspaper today that offers a fairly comprehensive summary of the various ways that Arab citizens are being intimidated by both the legal authorities and the benighted administrators of many of the major institutions where they are employed.

Said Abu Shakra is discouraged, but says he recognizes that at times like this, “People don’t want you to be in middle.” Yet that is precisely where Israel’s Palestinian citizens find themselves. They are the ones who held on and stayed after 1948, when two-thirds of their society fled or was banished from the newly established State of Israel, and I would argue that having them here is a blessing to Israeli society. Does that constitute incitement to terror?

“We have been in the middle all of our lives,” says an exasperated Said. “We have to be both Israelis and Palestinians. And today, the Israelis, the Jews, in the current situation, see only the wound they are suffering. They can’t see anyone else as being wounded.”

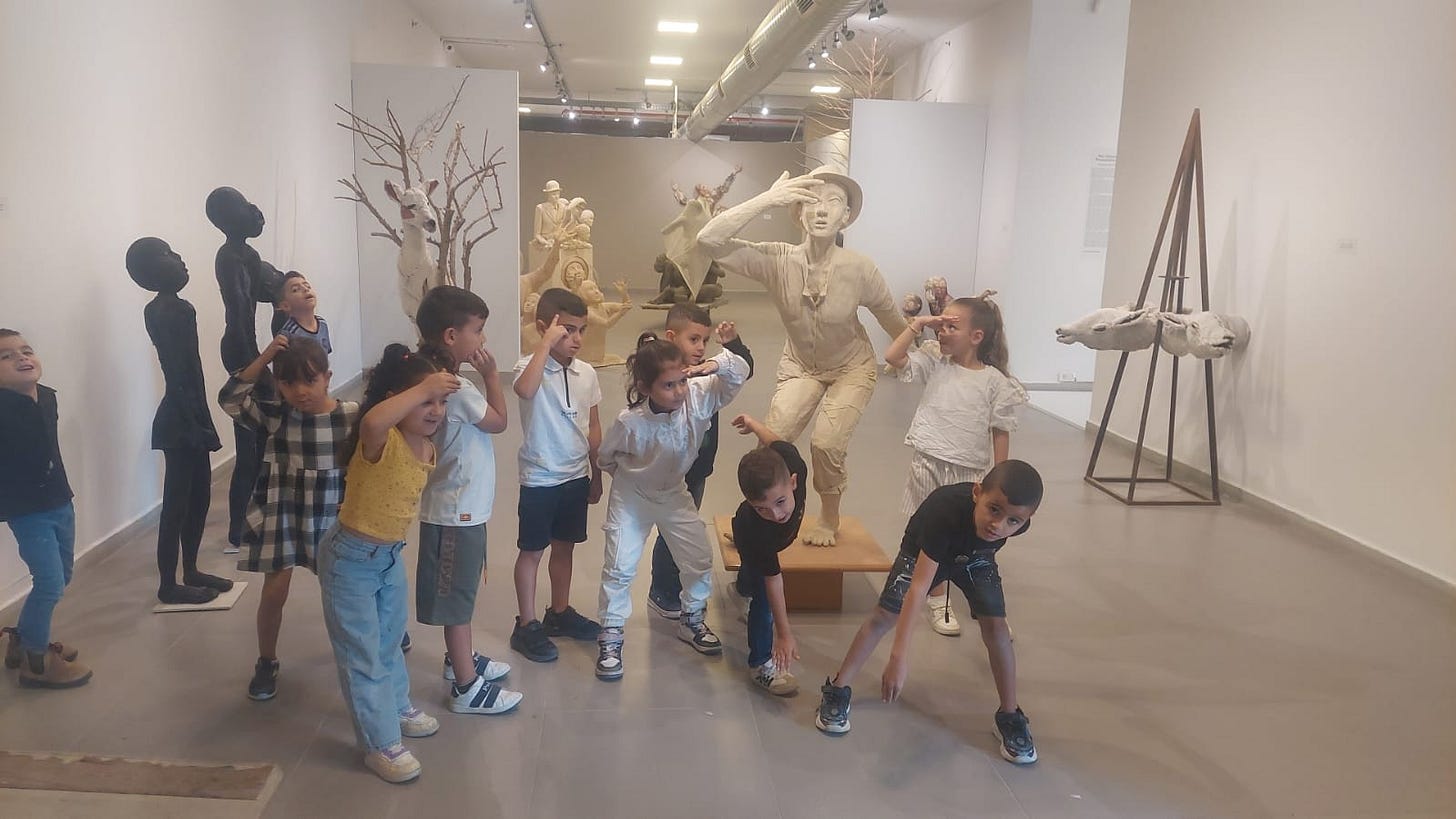

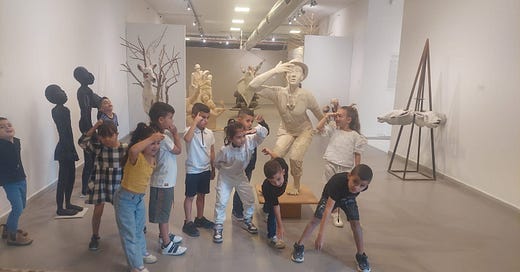

Best, therefore, he continues, “to let the rage pass” before speaking. In the meantime, though he has a staff of 15 permanent employees who were idle all month. Said will not lay them off (several of them are their families’ sole providers), but he did tell them last week that he would only be able to pay them half of their salaries for October, and asked them to work on programs that could be done with schools, many of which have returned to operating at least on a part-time basis. And indeed, a few days later, the first school groups visited a partially reopened gallery.

I have been struggling to find the words to express my appreciation of both you and your subject. To paraphrase a quote I heard from Micah Hendler, director of the YMCA Jerusalem Youth Chorus, your writing and Said's devotion to art may not be able to stop the war, but they remind us of and connect us to the humanity of one another, so that our common humanity may persevere notwithstanding the war. Thank you both.

Articulate, thoughtful, compassionate.... and so very very sad. Thanks, David