‘Light is the cheapest building material’

That’s just one of the architectural insights we get from Yael Melamede’s film about her Israel Prize-winning mother Ada Karmi-Melamede. We also get some thoughts about a design for life

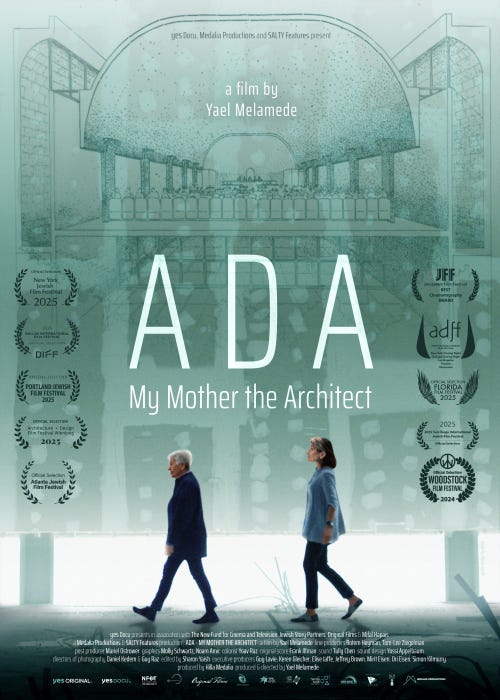

I first saw Yael Melamede’s very personal documentary film about her mother, the Israeli architect Ada Karmi-Melamede, when it premiered last July at the Jerusalem International Film Festival. The movie is now playing in a limited North American run, which hopefully will be expanded, and I urge you to see it whenever you have the opportunity. I explain why below.

“Ada: My Mother the Architect” is a film about architecture and design, of course, but no less, it is a film about Israel and its changing character; about family and the painful choices family members must sometimes make; about the role of women in society; and even about the ongoing ripples felt long after the death of people integral to our lives. It is touching, inspiring – and very sad.

That a 90-minute film can alight upon so many themes, and so successfully, is testimony to the aesthetic and emotional sense and sensibility of the filmmaker, Yael Melamede, whose subject happens to be her mother.

Ada Karmi-Melamede is the octogenarian Tel Aviv architect best known for designing, with her brother, Ram Karmi, Israel’s Supreme Court, which may be the country’s most acclaimed public structure. That and the other solo commissions that followed, which include the campus of the Open University, in Ra’anana, the visitors’ center at Ramat Hanadiv park, in Zichron Ya’akov, and the museum and city hall of the new Negev town of Ne’ot Hovav, all came after the age of 50.

Ada and Ram were heirs to both the talent and the reputation of their architect father. The Ukrainian-born Dov Karmi arrived in pre-state Palestine in 1921 and became part of a small group of Ashkenazi men who set the tone for the first generation of architectural design here. His own commissions included what is today called the Charles Bronfman (formerly Mann) Auditorium in Tel Aviv (co-designed with Ze’ev Rechter and Yaakov Rechter), and many residences in the International style in that city.

Dov’s granddaughter Yael also set out to be an architect, but she switched to filmmaking after her first assignment, which happened to be the renovation of her mother’s Tel Aviv apartment. “I never quite found my way,” she tells us in a film voiceover.

We also see the filmmaker onscreen frequently, in the role of interviewer (they go back and forth between Hebrew and English), often wearing a forbearing smile, as she attempts to coax a reluctant subject to answer one more question or elaborate on an earlier point. Ada obviously agreed to be the subject of her daughter’s film, but from its first frame, we see that it doesn’t suit her to talk about herself, or even to contemplate her daughter’s questions about her feelings.

Ada tells Yael that her sole memory of childhood is of sitting on her father’s shoulders during a Jerusalem snowstorm as he carried her to kindergarten (today, the schools would be closed in Jerusalem if the chance of snow was even 20 percent), “high up, someone to protect me.”

When Dov Karmi died, at age 56 in 1962, Ada says she was so bereft, “I thought I wouldn’t leave the house for a year.” At the time, Ada was newly married and pregnant with her first child, and she admits that she dreamt about bargaining to bring her father back to life in return for “giving up what I had in my belly.” (That would have been Yael’s older sister, Michal.)

Even though her working relationship with her brother, Ram, was often tempestuous (“I had a lot of wet eyes from him”), she speaks about him too in almost worshipful terms: “the most important architect in Israel, by far… a master.” (We see many stills and clips of Ram from over the years, and it’s amusing to see how dramatically his look changed from period to period, whereas the appearance of the even-tempered Ada doesn’t seem to have changed in at least 40 years.)

Five years after her father’s death, Ada, who had earned her degree in the family profession from the Technion: Israel Institute of Technology, followed her husband, business entrepreneur Amos Melamede, to New York, where he had been offered a job. She says that he persuaded her to agree to the move by telling her they would only be away for a year or two. Then, after they had been in the United States for a year or two, “he said, ‘You think we can come here and work for just a year or two? I can’t work that way.’”

Ada soon found work teaching at Columbia University’s school of architecture. Colleagues and former students testify to her talent as a teacher and her dedication to her pupils, but when she came up for tenure, after 14 years, she was turned down, and left without a job. Perhaps it was because she was a woman, it is suggested.

At the same time, work became available at the family firm, now led by Ram, back in Tel Aviv. Ada decided she would return to Israel on her own. Her daughter asks how it felt to leave her family behind in New York.

“Your father took care of you. I never really worried about you… I had a framework that made up for my losses.” She seems not to have considered her children’s losses.

It is never suggested that Amos and Ada were estranged or fell out of love. And when Amos, who by all accounts was not only brilliant and charming but also a loving partner and father, died of a stroke, at age 61, at his own birthday dinner in New York, in 1994, the loss was terrible. (Ada won’t talk about it on camera, saying, “These are bad questions.”) But by then, her children were mature adults, and she certainly wasn’t going to rejoin them in America.

Karmi-Melamede’s return to Israel had in fact opened the door to what evolved into one of the country’s most impressive and successful architectural careers. She doesn’t seem to have been seeking glory, however: For her, the work was always its own reward. Repeatedly in “Ada,” we see Karmi-Melamede, drawing pencil always in hand to illustrate a point, answer a question of her daughter’s – lucidly, profoundly, combining both theory and practice – and then impatiently appeal to Yael to let her get back to her work already.

Several years after her return to Tel Aviv, Ada and Rami had been invited to participate in a competition for the design of the new Supreme Court, to be built at the northern end of the Jerusalem ridge where the Knesset also stands, and underwritten by the Rothschild family’s Yad Hanadiv foundation. Although they were up against world-class architects with far grander reputations (Richard Meier, the I.M. Pei firm, Moshe Safdie, among others), the Karmi siblings prevailed, and the resultant structure, which opened in the fall of 1992, was greeted with near-universal praise and appreciation.

Just as a well-designed building that knows how to admit light judiciously can give the visitor a sense of well-being, every element of this film feels right. Deserving of special note is the original music, by Frank Ilfman, which is alternately wistful, playful and mournful, as required. The visual design too has the clean intelligence of a Karmi-Melamede building – never bombastic, but clever and humane. The director often employs a split screen, where on one side, we see the architect’s hand as she is drawing, and on the other side a profile shot of her talking.

And it is the combination of Ada’s words and drawings that make this film extraordinary. She explains that in her designs, “I am looking for roots,” and her ambition had always been to create buildings that “hit the ground and penetrate it, and take root.” She is convinced that such structures are too rare today. Instead a building, or at least an urban skyscraper, is merely “a technological envelope, which has to do with glass and with transparency.” And these, she says, “are boring.”

Contemplating and entering a building, explains Karmi-Melamede, should be a journey. “You went into a building, you went from point A to point B, and the route you followed had architecture. … Today, in the open architectural plan, there is no route.” There is just the arrangement of the furniture, “And when the space changes all the time, it doesn’t build memory. So we live in buildings that basically don’t build … any shared memory.”

The roots metaphor has additional personal meaning for Karmi-Melamede, who explains that she feels that “Even though I lived many years abroad… my real home is here... It’s also true of the language. Language is a homeland, no less than the place.”

And then there is the question of light and shadow. “I always think that with one beam of light that falls in the right place, it’s possible to change everything.” This is especially the case in Israel where, as Karmi Melamede explains, “the light is so intense and bright” that it demands modulation. “If you use indirect light, and you allow it to enter and bounce from side to side when it enters the room, it completely changes the quality of the materials. It creates a certain softness in the room.”

A former employee from her office tells the filmmaker how one of the first things that stayed with her from working with Ada was the boss’s revelation that “light is the cheapest building material.”

Sometimes you’re not sure if she’s talking about design or life – and then you understand that she’s talking about both.

At one point, when Ada seems set to shut down an on-camera session, her daughter abruptly asks her to “draw a cat.” It turns out that Ada used to decorate the letters she sent to her daughter with sketches of cats, drawn with simple, often geometric shapes that beautifully capture “catness.” The mother, caught off-guard by the request, relents, and allows the interview to go for another minute before she dismisses the daughter.

“Ada: My Mother the Architect” ends with a letter, its envelope adorned with a cat viewed from the rear, written by Ada to “Yaelussi” three decades ago. It’s not clear what was happening in Israel at the time, but she writes to her daughter in New York that, “I often think that the last few weeks have been so terrible [here] that we are not going to emerge in one piece, that we are forever divided here, and since the only glue is the past, there is not great chance for the fresh, courageous and imaginative minds to come out and rise above the chaos.”

“I almost could have written it today,” says Ada. At the time their video conversation is taking place, Israeli society was under assault from its own government, which was trying to effect a judicial coup.

“It’s about the power of the Supreme Court to [overrule] the Knesset,” Ada explains about the Israel’s main 2023 political battleground. The film was apparently completed before October 7 of that year.

Yael asks Ada how she feels about having the institution whose home she designed be at the epicenter of the country’s culture war. Ada, being perhaps overly literal, responds that the controversy is really over “the future of the country, which has nothing to do with the building.”

Of course, even that’s not entirely accurate, as we have learned earlier in the film. In their thinking and planning for the building, the Karmis were well aware that the Supreme Court is the keystone of Israel’s imperfect democracy, and thus they gave weight to the symbolic role of nearly every element of their design. (For inspiration, she recalls, Ram went back and read the Bible, while she read a book about the Supreme Court by its former president Aharon Barak.) For example, former court president Barak tells the filmmaker that he “never liked the entrance to the U.S. Supreme Court with its big columns, and you look like a tiny, tiny person walking into the court.”

In contrast, says Barak, here, you come in, and you walk up a narrow staircase, and when you emerge, you face a panoramic view of Jerusalem. “You are the center. You enter your court.” Unfortunately, many Israelis, perhaps a majority, no longer feel that way about the court, having been convinced by their leaders that the country’s legal system, at whose pinnacle stands the High Court, is controlled by a supercilious, elitist minority.

Perhaps saddest, on the personal level, is that when Yael asks her mother if she wishes any of her children had come back to Israel, Ada tells her no. The country, she says, is “terribly sick.” She adds that, “I also think that one of the reasons I’m connected here has to do with stuff that was here before, not stuff that is here now. I love it because of what doesn’t exist anymore in a real sense, for me.”

Viewers of this movie may well emerge from a screening feeling a melancholic nostalgia. One shouldn’t let those feelings lead to hopelessness. As long as there are principled, visionary people like Ada Karmi-Melamede in Israel – there are, and not all of them are 88 – there is reason to take heart.