Is a better future even possible?

In their superb new book about the long history of Israeli-Palestinian peace talks, Hussein Agha and Robert Malley want to understand why they were perpetually doomed to failure

This book review first appeared in the October 2025 issue of The American Prospect magazine, and online at its website.

Michael Sfard has long proclaimed that someday, Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories will come to an end. The courageous Israeli human rights lawyer never predicted how many decades this would require, nor how many lives would need to be sacrificed before Palestinians and Israelis would each have control of their lives, but simply argued, as he told me in 2018, how in his understanding of history, “regimes that are fundamentally subjugating people, stripping them of rights … are regimes that by definition are not sustainable.”

Today, Sfard himself would likely agree that his vision is further from realization than ever. The extent of death, destruction, and overall human suffering that both Israelis and Palestinians have visited upon themselves and each other since October 2023 challenges human comprehension. Two years ago, to most of us, at least, such barbarities would have been unthinkable.

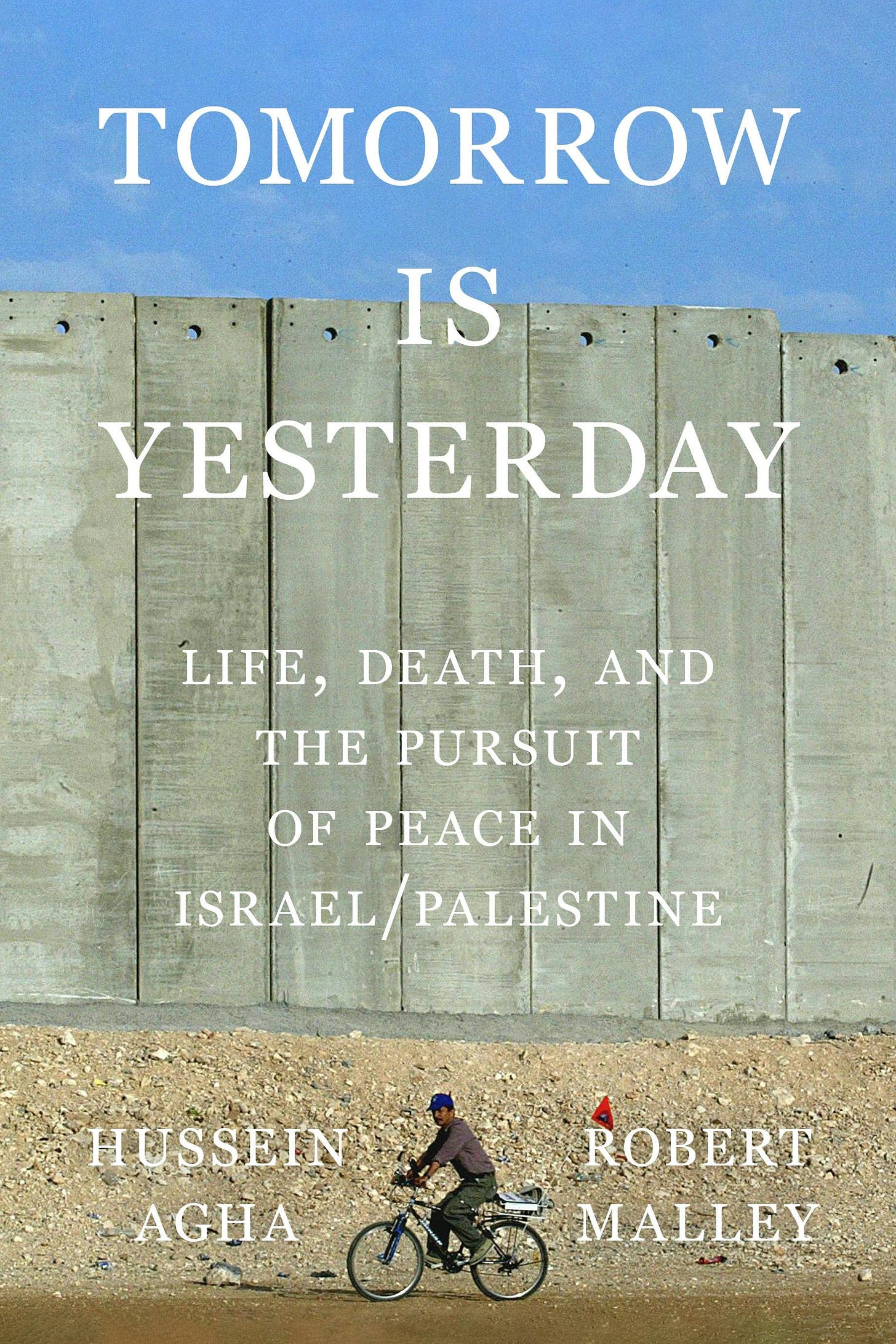

Not to Hussein Agha or Robert Malley, however. In Tomorrow Is Yesterday, they as much as assert that the latest round of violence, extreme as it may be, is not essentially different from the brutality that has accompanied the conflict for the past century. Which is why they have chosen to publish what is essentially an analysis of how all previous efforts to negotiate peace were doomed to fail, and why the two warring parties were nonetheless willing at various times to acquiesce to plans they found unsatisfactory. Giving in, they say, was easier than grappling with the fundamental questions that truly define the conflict.

Yet leaders of democratic states earnest in their desire to end the bloodshed, and to do so decisively, are again talking about two states, and about diplomatic recognition of the Palestinian one. The United States is offering a different alternative, but one that is even worse than no solution at all. Thus the urgency, from Agha and Malley’s perspective, to resist returning to the failed assumptions of the past, and to urge for consideration of a different approach to peacemaking. The two are former negotiators who were both involved, over many decades, in attempts—all of them ultimately failures—to resolve the conflict. Both also have deep personal connections to the region.

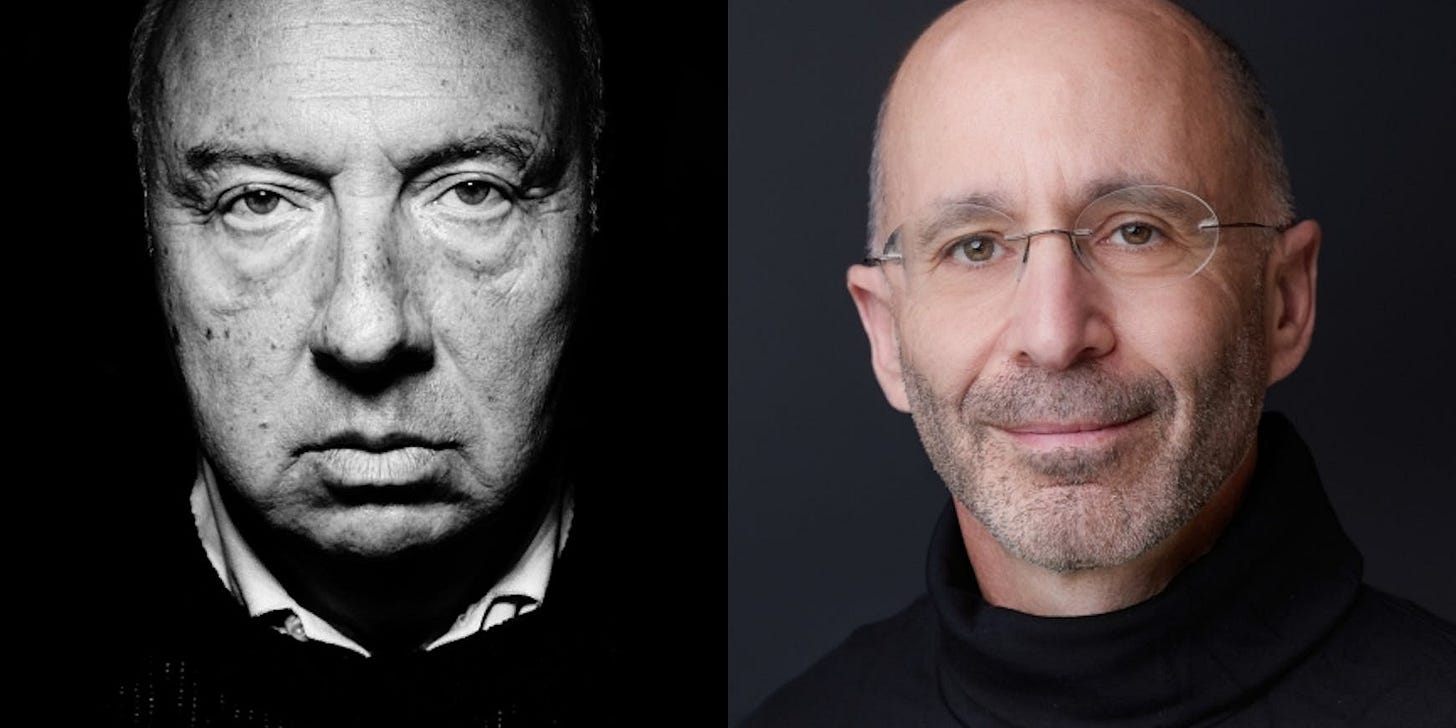

Hussein Agha, in his mid-seventies, is an Oxford-educated writer who grew up in a Beirut home that was filled with books, art, and music created by Jews, and often visited by his Lebanese-Iraqi-Iranian father’s Jewish colleagues in the rag trade. As an adult, Agha became an adviser to Yasser Arafat and later to Mahmoud Abbas—Arafat’s successor as president of the Palestinian Authority—and participated in many negotiations with Israel over the years, both formal and unofficial.

Malley, born in 1963, is the son of a Syrian-Jewish globetrotting journalist who supported nearly every national liberation movement on Earth—other than Zionism. The authors write that the main impact of Simon Malley’s being Jewish “seems to have been to provide him reason to be an Arab nationalist of the fiercely secular, anti-Zionist sort.”

Rob, as he is generally called, was raised in Paris, where in high school he debated classmate Antony Blinken on the question of Israel-Palestine, with Malley defending the Palestinian position. Generally, though, he says he rejected his father’s black-and-white view of the conflict, and became convinced that Zionism and Palestinian nationalism were “two competing national movements in need of some kind of coexistence.” That is the approach that characterizes his and Agha’s book, which is not intended to be a brief for one nation or the other.

Malley worked in the Clinton, Obama, and Biden administrations, both on the Iran nuclear issue and as the organizer of the 2000 Camp David peace conference. He also worked for close to two decades, off and on, at the nonprofit International Crisis Group, including three years as chairman and CEO of the political analysis organization.

Although part of Tomorrow Is Yesterday is dedicated to making the case against the two-state solution, the authors are not especially interested in proposing alternative frameworks, and devote only a few pages toward the book’s end to a cursory listing of ideas for possible federation, confederation, or even “two superimposed states.” While partition into two sovereign entities may still seem like the only logical alternative to outside do-gooders, considering that neither side is currently in the market for peace plans, it may make sense to let the imagination run wild with more unconventional ideas for the future.

The authors are mainly intent here on arguing that while the Israelis and their American sponsors (who come in for the most extensive criticism in the book) were looking to make what was in effect a real estate deal that would leave Israel safe and secure, the Palestinians were seeking justice. For them, the “notion that Israel was ‘offering’ land, being ‘generous,’ or ‘making concessions’ seemed … doubly wrong—in a single stroke affirming Israel’s right and denying their own. For the Palestinians, land would not be given. It would be given back.”

Fundamentally, the conflict was about much more than land: It was about the roughly 300,000 of the indigenous Palestinians (and their descendants) who went into exile as a result of Israel’s creation, and the question of how the loss of their homeland and property would be recognized, if not compensated for. It was also about Palestinian insistence that Jerusalem, meaning the Arab, eastern half of the city, including the Muslim holy sites in the Old City, serve as their capital.

For even the most sympathetic Israeli politicians, by contrast, peace talks were expected to begin with discussion of the fate of the territories conquered in the 1967 Six-Day War: the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and maybe Jerusalem. Anything other than that, such as a demand for recognition of refugees’ “right of return,” was tantamount to “reopening the 1948 file,” meaning negotiating the very basis for Israel’s establishment, which the international community had already agreed upon in 1947. That was never going to happen.

Though the authors don’t make this point explicitly, it was Yasser Arafat who was largely responsible for this state of affairs, after he agreed—implicitly in 1968 and explicitly two decades later—to have the PLO Charter changed so as to accept the idea of two states, with the Palestinian one to be formed in lands occupied by Israel in 1967. This may not have reflected a particular ideological vision, but Agha and Malley suggest that Arafat was principally interested in maintaining Palestinian unity. At this he succeeded, and even when his decisions caused internal dissent and anger, his “preeminent position was seldom questioned.”

Arafat’s gradual adoption of the two-state concept is what made it possible for Israel to begin speaking with Palestinian representatives, but it also meant that when the Oslo process began, in 1993, the sides leapfrogged over cardinal issues that spoke to the essence of the conflict.

That may have resulted in what seemed like progress in negotiations, write Agha and Malley, but in fact disregarded that it was “impossible to resolve the conflict in the present without pronouncing some judgment on its past. Palestinians insist on acknowledgment of, and redress for, the Nakba; Israelis look for genuine acceptance of their material and spiritual connection to the land; each desires accountability for what the other has inflicted on them; both have 1948 in mind even as they speak of 1967.”

The authors put their finger on the essence of the problem in this way: “Palestinians hoped they could achieve their goals even as they persisted in denying the Jewish people’s historic attachment and entitlement to even part of the land. Israelis trusted that if they granted Palestinians some kind of restricted governing role in a portion of territory, the whole problem would fade away. It is only a slight exaggeration to describe the talks as a confidence game, a tacit agreement to elude the historic core of the matter through disingenuous ambiguity.”

(About the wily and elusive Arafat, the authors write: “He never read a proposal he rejected; never read one to which he agreed, either. If you knew how to listen, you could discern the truths he dispensed without meaning a word of what he said.” To which they later add that violence “was merely one among the few instruments at the Palestinians’ disposal, neither more nor less legitimate than others.” The Arafat they describe might make for a fascinating literary figure, but not one on whom you would want to depend in negotiating a life-or-death contract. And since 2004, when Arafat departed the stage, no Palestinian leader has wielded similar authority among his people.)

The point is not so much, then, that the two-state idea was always bound to fail (although the authors are persuasive in arguing that neither side ever truly believed in it), but rather that successive attempts to implement it, beginning with the Peel Commission recommendations of 1937, and continuing with the U.N. plan in 1947 and on through the Camp David summit in 2000 and beyond, ignored both sides’ fundamental needs and fears.

To those who say the various two-state plans always failed because of “bad luck”—“Barak had the intellect but lacked the subtlety and empathy to match; Arafat possessed authority but could not fashion himself a statesman; Sharon left the scene too soon or saw the light too late; Olmert was farsighted, but corrupt, Abbas overly cautious, the Palestinians divided”—Malley and Agha cite the blues musician Albert King, who famously sang, “If it wasn’t for bad luck, I wouldn’t have no luck at all.”

The authors devote significant space to analyzing the car crash that was Camp David. In their telling, Arafat did all he could to convince Clinton that the time was not yet ripe for talks. Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, however, had his reasons for insisting on going ahead with the summit, while for the U.S. president, the hourglass was running out on his second term, meaning that it was now or never. When the talks failed, Clinton joined the Israeli premier in pinning the blame on Yasser Arafat, and that is the version that is most widely accepted today. It says that the Israelis presented the Palestinians with the “most generous offer” they ever received, and the Arabs turned it down. That, combined with the outbreak of the intifada just a few months later, characterized as it was by a wave of shocking suicide bombings, served to permanently convince most Jewish Israelis that peace would never be possible with this adversary.

In this telling, once again the Palestinians had made the wrong choice, and forever after, “Camp David” would serve as “the two-word answer to all manner of difficult questions about Israel’s actions, behavior, and intentions. When Israelis strike at Palestinians, a reaction stands ready: The Palestinians had their chance. They blew it.”

It’s not obvious that one can expect “justice” to emerge from a diplomatic negotiation where details of an agreement are being hammered out, but it is clear that neither Palestinian nor Israeli leaders ever laid the necessary groundwork by which their people would understand and internalize the legitimacy of the other side’s narrative, which is what was required to make any legal deal receive their support. That is how it is that in the Israel of 2025, we have a government that can deny that the Palestinians suffered a catastrophe (the literal meaning of “Nakba”) in 1948, and it is how there has never been a serious national debate over the fate of the territories and the settlements.

On the Palestinian side, the corresponding fear or unwillingness of the leadership to convince their society of the legitimacy of the Jews’ claim to a national home in the Land of Israel explains in part how there can be widespread support for Hamas and more radical Islamic organizations, which are constitutionally incapable of accepting Israel within any borders. No wonder Israelis have always been reluctant to make the necessary concessions: “When violence rages,” the authors write, “they cannot afford to consider far-reaching compromise. When it fully subsides, they no longer need to.”

Tomorrow Is Yesterday is a short book, only a little over 250 pages, and it does not purport to be comprehensive. Still, it is a shortcoming that in its criticism of successive U.S. governments—for failing to play the role of honest broker, for failing to press Israel at critical points, for going along with arrangements that turned the Palestinian Authority into a subcontractor for Israel’s security, and thus eroded its credibility in Palestinian society—it doesn’t mention the role played by the Jewish establishment in America, in particular AIPAC (the American Israel Public Affairs Committee), in twisting arms in every branch of the U.S. government to acquiesce to Israel’s demands. The authors acknowledge the internal politics that Israeli and Palestinian leaders had to contend with, but don’t take it into account sufficiently when it comes to American politicians.

Agha and Malley also provide a concise but illuminating history of Hamas and of its own civil war with Arafat and Abbas’s Fatah. But while they acknowledge that Hamas’s ideology prevents it from ever conclusively coming to terms with Israel, they do insist that Israel missed several opportunities to come to a long-term cease-fire with Yahya Sinwar, the mastermind of the October 7 attack, which might well have prevented that particular bloodbath. But in a book that so convincingly argues for dealing with fundamentals, and resisting the temptation to accede to quick fixes, that advice, even offered retroactively, seems to contradict the main message.

Overall, though, Tomorrow Is Yesterday deserves widespread attention and praise. That includes appreciation for the writing itself, which sometimes sings. If it is exceedingly difficult to see grounds for optimism in Israel-Palestine right now, it is reasonable to suggest that Hussein Agha and Robert Malley would not have written their book if they did not think a better future was possible. For the people who live here, there truly is no alternative to believing that and to working toward it. If the authors’ main contribution has been to conduct a “debriefing,” in which they identify the failings of past efforts, we will have reason to thank them, as the popular Israeli song from 1967 has it—“if not today, then tomorrow, and if not tomorrow, then the day after.”

Thank you for writing this - I heard them interviewed, and I really struggle with their approach ('if we couldn't do it, it couldn't be done'), and with the lack of historical and geopolitical context in which they discuss the conflict (as if the conflict is singular in nature, without context of other struggles and questions of self-determination). I appreciate your framing ...gives me less of a reason to be frustrated!