'I was unprepared for the amount of hatred I witnessed in Hebron'

Lawrence Wright had turned in his semi-apocalyptic novel about a new Israeli-Palestinian war before October 7. Just don't call him a prophet

(This article appeared originally in Haaretz English Edition.)

Lawrence Wright doesn’t like it when people tell him he’s a prophet. But he does have a spooky tendency write about cataclysmic events before they occur.

For example, in the film “The Siege,” for which he wrote the original story and co-wrote the screenplay, federal agents (played by Denzel Washington and Annette Bening, among others) in New York are confronted with an Islamic terror cell that launches a series of increasingly destructive bombings in public spaces and threatens even worse if their demands aren’t met. That may not sound so prescient – except when you consider that the film came out three years before 9/11.

More remarkable timing must be attributed to Wright’s recent “The End of October,” a novel that imagines a deadly, previously unknown virus that escapes from a refugee camp in Indonesia, and spreads with lightning speed around the world, threatening to annihilate humanity. That book was released in late April 2020, shortly after COVID-19 shut down large parts of the planet, but Wright had finished writing it long before any virus-carrying bat – if that indeed was the guilty party – flew out of a wet market in Wuhan, China.

Wright’s just-released now novel is “The Human Scale,” which is based in Hebron in the early autumn of 2023 with a plot that involves messianic Jewish settler-terrorists, their local Hamas counterparts, and the Israeli officials whose job is supposed to be fighting them both. In the final chapters, however, the story moves to Gaza, from where Hamas launches its massive October 7 attack on Israel.

In this case, Wright had finished a draft of the book prior to October 7, and then revised it after the start of the real-life Gaza war. But the darkness of the book’s tone, and the sense of impending, inexorable doom that pervades it – a sense of helplessness that seems to be shared by author, readers and the novel’s characters – leaves an Israeli wishing that his country’s leaders had been as sensitive to developments in the territories as closely as Lawrence Wright was in the years leading up to October 7.

Boundless curiosity

Wright’s day job, as it were, is actually journalist, writing long reported features for The New Yorker magazine. But he refuses to stay in the nonfiction lane and has also written four novels, the screenplays for five films (both documentaries and features), and has even appeared on-stage as himself. Maybe it is his boundless curiosity and creativity that impel him to go beyond the facts.

Wright, 77, was born in Oklahoma, raised largely in Dallas and lives today in Austin – the state capital, the home of the University of Texas, and in recent years the home base for Tesla as well as numerous other high-tech firms large and small.

The city is also famed for its live-music scene, which – naturally – Wright also participates in, playing keyboards with local blues band WhoDo. He has written extensively about his fascinating and infuriating home state, about race and poverty issues, the Church of Scientology (“Going Clear,” a 2013 book that was later adapted for the screen by documentarian Alex Gibney) and, most prominently during the past two decades, about religious extremism in the Middle East.

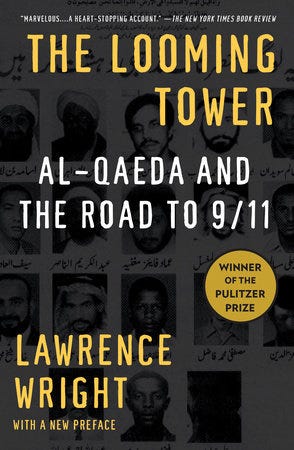

His 2006 book “The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11” won him the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction. A reporting trip to Gaza in 2009, following Israel’s devastating Operation Cast Lead, led to a lengthy New Yorker piece in November 2009 that is as good a concise introduction to the history of the Strip as anything I’ve read. (Read the article today and, in retrospect, you will realize that no one should have been surprised by anything that’s happened in Gaza during the past decade and a half.) A year later, Wright turned that article into a one-man play for New York’s Public Theater. It also had a limited run in Tel Aviv in 2014.

The solo show about Gaza went by the same title as Wright’s new book, “The Human Scale.” That might be confusing, but his insistence on reusing the title hints as one of Wright’s great strengths as a journalist: his interest in people and his ability to connect with them on the personal level, whether they are political leaders, guerrilla warriors or the common folk who end up paying the price for the decisions of the former. As he told Haaretz, he attempts to give the people he writes about “a full life, so that you understand what is lost when they’re sacrificed.”

At the center of the new novel is Tony Malik, an FBI agent of Palestinian descent. He is still recovering from having been in the wrong place when a terrorist bomb intended for a transatlantic flight was detected (by him) but detonated while being disarmed. Desperate to return to active duty, a partly disabled Tony accepts a minor assignment to meet with the chief of Israel’s police station in Hebron, after the latter has asked for a meeting with an American official to discuss a sensitive topic. Tony plans to combine his work trip with attending the wedding of a Palestinian first cousin in Hebron, in what will be his first visit to the place where his father was born.

Tony and the police chief do meet, but unfortunately the Israeli is assassinated a short time afterward. After he shakes off the suspicion that immediately falls on him – he is, after all, an Arab and this is Israel – he joins up with the second-in-command in the Hebron station, in an attempt to unravel the killing and prevent a larger explosion of violence.

In that sense, “The Human Scale” is a buddy story about a Palestinian and a Jew who overcome their mutual suspicions and the natural tendency of humans to jump to conclusions when they are confronted with facts and evidence that don’t support the usual-suspect scenario.

Since the book ends with the October 7 massacre, I will not be revealing too much if I say that it lacks an upbeat conclusion. There are some small victories, if only in the sense that certain characters act honorably and in so doing prevent additional disasters. But this is a novel whose cast of characters is much shorter at the end than when the story opens.

Haaretz spoke with Wright on the eve of the book’s publication, in part in the hope of learning what possessed him to write a novel about such a relentlessly dark subject. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

‘Plausible and real and immediate’

Q: What is it about this place, this region, that keeps drawing you back?

A: “As a young man, I taught English at the American University in Cairo, in 1969-1971. That was my first exposure to the Middle East and its truckload of problems. Teaching young Arab and Egyptian men and women was a great joy for me. I knew nothing about that part of the world. But it was a life-changing experience in many respects.

“I would never have written the movie ‘The Siege,’ which is about terrorism coming to America, if I hadn’t had that experience, and I would never have written ‘The Looming Tower.’ That future wasn’t apparent at the time, but it did draw me into the region.

“I think the first time I went to Israel was in 1997. I was part of a State Department package that was talking about American publishing in Cairo and Jerusalem. It happened that there was a lot of activity in Hebron at the time – a lot of stone-throwing and stuff like that – so I hired a guide to take me there. I was unprepared for the degree of hatred manifested in Hebron.

“That planted a seed that eventually became the story of ‘The Human Scale.’ I’d explored the problems in nonfiction, but maybe another way of getting at the truth is to write fictional stories as a way to explore the mentality and personalities of the people that I have run into over the years. So that’s where Yossi Ben-Gal came from, the deputy chief of police in Hebron.

“Then I wanted a Palestinian character. When I was writing ‘The Looming Tower,’ I met some Arab-American FBI agents, and so I drew from that experience for Tony Malik. These [Yossi and Tony] are two individuals who are similar in certain ways, but the very powerful tides of history and culture and ethnicity have pulled them apart. And the experiment, the question that I pose in the novel, is: Can these two men, despite all of the forces pulling them apart, can they find a way to trust each other?

“I actually turned in a draft [of the novel] in August 2023. And it ended with a war. But it wasn’t a war that was transformational in the way that October 7 was. And now I was faced with a problem: October 7 threatened to overwhelm [the book]. And I finally had to go back and rewrite it with October 7 in mind.”

It did occur to me, especially when I remembered reading “The End of October” about a global pandemic: Either you’re lucky, or you have certain prophetic powers…

“Stop. Stop on that. I just won’t address it. That follows me around all over the place. I am not a prophet. The difference between what I do in fiction and what I do in nonfiction is very slight, in some ways.

“When you’re a reporter or journalist, your main question, essentially, is what happened. As a screenwriter or a novelist, you’re asking what could happen. So we’re dealing with similar materials. One is a work of imagination, and the other a work of nonfiction. But the truth is that I research my fiction as intensively as my nonfiction, maybe more so. I don’t want the reader to be hovering over the text and saying, ‘Oh, he got that wrong.’ Or, ‘That’s not right, that would never happen.’ I wanted to make it as plausible and real and immediate as possible.”

You also pack in a lot of straight history. Early in the book, you have a chapter titled “A Guide to the Holy City,” in which you provide over the course of several thousand words a concise history of Hebron, so that the reader will understand just how deeply rooted the competition over the city is, and how important a role religious belief plays in it.

“You’re right to point out the [recounting of] history – the history is a large part of the source of the problem. If you go to the scene in the mosque [in the Tomb of the Patriarchs] in Hebron, where Jamal is showing around Malik, and they bring out this old man with the fire extinguisher who demonstrates how he bashed in the head of the killer [Baruch Goldstein, who murdered 29 Muslims there in 1995] – that happened to me! That was back in 1997. They brought out this old man and he reenacted how he used this fire extinguisher to bash in the head of Baruch Goldstein. Moments like that were in the bank in the back of my mind. And when I sat down to write, they came back to mind.”

For me, the thing that distinguishes you is that you have compassion and sympathy – and also criticism and frustration – for most of the people you write about. You’re not writing a brief for the settlers or for the Palestinians. But am I right in thinking that looking at the situation today, one of your principal responses is a feeling of hopelessness?

“I do think that my feelings are equally divided between Palestinians and Israelis. I acknowledge that this is a tragedy that happens to both sides – and that’s what makes it so durable. But on the other hand, it’s been frozen for so long, and there’s so much that’s in the air right now. Sometimes, it seems like there may be a better opportunity for peace than at other times when the – what was the word they use in Israel, ‘the concept’? --"

Yes, the “kontzeptzia.”

“-- had frozen everything. Maybe unfreezing, things become fluid again. Still, being hopeful in the Middle East is never a sure bet. So, I grieve for the turn things have taken. And I long for voices that are willing to take a risk for peace – although so far I haven’t heard them.”

I’m sure you are asked about this a lot, but I think it’s unusual that you work in so many different media. Why don’t you just stick to journalism?

“It’s all storytelling. I acknowledge that there are differences, and that it seems to be unusual. But preparing, oftentimes in my research into an area, well, like terrorism, I start by writing articles. And then a nonfiction book. You know, the truth is that [writing about terrorism] started with fiction, with “The Siege” – that’s where this whole prophet nonsense got started.

“I asked what would happen if terrorism came to America – to New York – as it already had to Paris and Tel Aviv and London. That’s the way that a novelist or a screenwriter writes, asking what would happen. And that was at the basis of it. And then, holy shit, it came true in some awful way [three years later].”

I remember seeing The Siege: It was in 2001, shortly after 9/11. So I forgot that it anticipated 9/11. When it was originally released, was it successful at the box office?

“In 1998, it was not successful. And I’ll tell you why. Muslims were offended by an Islamic terrorist and they boycotted the theaters. People don’t want to go to a movie when there’s a picket line outside. And so it was a bust. And then after 9/11, it was the most rented film in America – that along with a documentary called ‘The Prophecies of Nostradamus.’

“I liked the movie quite a lot. The acting, the directing [by Ed Zwick], everything, I was very pleased when it came out. But the first time around, people just missed it. Now, it’s still shown on TV, especially on [the anniversary of] 9/11 – it’s a kind of holiday movie.”

Has there been any interest in the film industry in optioning “The Human Scale”?

“Oh yeah, there’s been some talk of it. But I’ve had some experience in Hollywood and the lesson I’ve learned is: You don’t buy the house until you’ve eaten the popcorn.”

Have you been back to Israel since October 7?

“No, I haven’t. The last time I was there was in February 2023. At the time, I was close to finishing the draft, and I went there mainly for fact-checking purposes. You’ve probably seen this on your social media, but while I was in Hebron, Issa Amro [a Palestinian human-rights activist in the city] was showing me around. And he was attacked by a young IDF soldier, right in front of me. And I was with this Belgian photographer and she filmed it, and we posted it. It’s had this viral life that’s a little astonishing to me.

“But that was a scary moment. First of all, it was amazing to think that two Western observers are standing there, filming this, and yet this soldier felt entitled to abuse this guy. I thought: If we hadn’t been there, and if eventually his fellow soldiers didn’t pull him away, he would have killed him. It was a very, very shocking experience. That’s one of those moments when you feel like, can fiction actually reach the level of trauma that real life actually does?

“The head of the IDF Central Command called me in to explain that this isn’t their policy. But the truth is, these kind of assaults happen all of the time – just when [the perpetrators] aren’t being observed.”

I very much appreciated “The End of October.” I read it before publication, just as COVID was beginning to sweep across the world. It was apocalyptic. And “The Human Scale” has a similar apocalyptic feel. Is that the way you are? Are you a pessimistic guy?

“If you take those two examples, I think you could make a case for it. But the novel that came in between those two is a comedy, set in the Texas House of Representatives. Of course, I think that’s a hopeless cause too.

“That book is called ‘Mr. Texas.’ I had a lot of fun writing it. I’ve lived in Texas a long time. I’ve seen under its skirts. So I had to write about it.

“But you know, I try to look at the world the way that it is. At least the way it appears to me. And as close as I can come – not just in my nonfiction, but also in my novels – to make it real, that is my goal.”

Always illuminating! I look forward to your blog.