'Excuse me if I’m disturbing your ethos'

Prof. Mustafa Kabha wants both Jews and Palestinians to know all there is to know about the history and geography of their shared homeland. And for Jews not to be scared of the word "Nakba."

If the four Arab political parties that made up the now-defunct Joint List succeed in overcoming their differences and reuniting before the next election, it will in large part be thanks to the mediation of Mustafa Kabha.

Kabha is neither a politician nor a lawyer, but rather a professor of history. He has unique standing in Arab society that makes him a natural to serve on the so-called Consensus (or Reconciliation) Committee. An informal body of distinguished men, the committee was midwife to the birth of the Joint List in 2015 and is working hard today to bring about its revival. According to former Hadash MK Yousef Jabareen, Kabha possesses “impressive abilities at mediation and peace-making” that have placed him at “the center of the activity of the Consensus Committee.”

At its peak, during its relatively brief outing as a coalition of Israel’s four principally Arab parties – it disbanded for good in 2022 – the Joint List attained an unprecedented 15 seats in the Knesset. Today, the three of its parties that made it into the current Knesset have a mere 10 seats between them.

Polling has for years shown that the Arab public in Israel wants its politicians to be united, and that voters will come out in larger numbers if that is the case. But the differences that broke up the Joint List are not only matters of ego or even politics, but also reflect the way the different parties understand their identity as Palestinians with Israeli citizenship, and what their responsibility is to the larger struggle of Palestinians to end the occupation, among other goals.

Prof. Kabha is a member of Israel’s academic elite – he is a professor at the Open University, and former chairman of its Department of History, Philosophy and Judaic Studies – but he is also a keeper of the flame of Palestinian identity in the wake of the Nakba – the Arabic term, meaning “catastrophe,” by which Palestinians refer to the impact on them of Israel’s founding. Kabha is, for example, widely recognized for being the go-to guy for the most up-to-date list of Arab villages that were destroyed during the 1947-49 war.

“[Benny] Morris spoke of 362 villages,” explains Kabha, “[Walid] Khalidi wrote about 418, Salman Abu Sitta said there were 532; I say 577. And I think there are others. I’m still looking.”

Prof. Kabha’s standing in Palestinian-Israeli society derives from other accomplishments and pursuits too. Since 2021, for example, Kabha has been president of the state-sponsored Academy of the Arabic Language, which among other things, has published trilingual (Arabic, Hebrew, English) lexicons for professionals working in such fields as communications, citizenship, education. Currently, the academy is working on a lexicon for the dental profession.

Kabha, 62, wrote his master’s thesis about Egypt during the War of Attrition with Israel (1969-70), and earned his doctorate writing about the Palestinian press during the years 1929-39. All told, he has written or edited more than 30 books, which include, in English, the 2013 “The Palestinian People: Seeking Sovereignty and State,” a political history, and, more recently, “The Lost Orchard: The Palestinian-Arab Citrus Industry, 1850-1950,” co-written with economist Nahum Karlinsky (worth owning if only for its cover, which reproduces a painting by Sliman Mansour of an idyllic orange orchard of yore). He also has published an encyclopedia of place names in the Land of Israel/Palestine, and continues working on a compilation of the genealogy of Palestinian families.

If you ask him about the history of his own family, for example, he can tell you that he has traced the name “Kabha” back to the seventh-century Arabian peninsula, which his forebears left as part of the Islamic Conquest of the region. In their case, they settled in the area around Hebron, (he can tell you in which villages), before moving, during the Ottoman period, to a number of locations in Wadi Ara, in the country’s center, including his home village, Umm al-Qutuf.

Kabha’s explorations of the land have earned him a reputation as a guide (“I know every tree and every bush, and every plant that grows in this country,” he told me some years ago, perhaps exaggerating a bit).

“If you follow his stories on Facebook, you see he’s in the field all the time, and he posts photographs all the time,” of the ruins of Palestinian villages he has visited, says Dr. Arik Rudnitzky, a researcher in the Program on Arab Society, at the Israel Democracy Institute, in Jerusalem. “Prof. Kabha personifies the project of reviving the Palestinian memory,” which has given him “the image of a loyal, courageous, authentic representative of the Palestinians, above any political agenda,” Rudnitzky adds.

You could see him leading a group of students in the recent documentary film “1948: Remember, Remember Not” – if the public broadcaster Kan, which produced it, were to overcome its reluctance to subject Israelis to such “sensitive” content while the country is still at war. Neta Shoshani’s beautifully produced film is an eclectic history of the War of Independence, as captured in primary sources, both personal and official, from both sides of the conflict: contemporary diaries, letters, documents, films and photographs. Originally scheduled for broadcast on Kan Channel 11 in the fall of 2023, its screening was put on hold indefinitely after the attack of October 7.

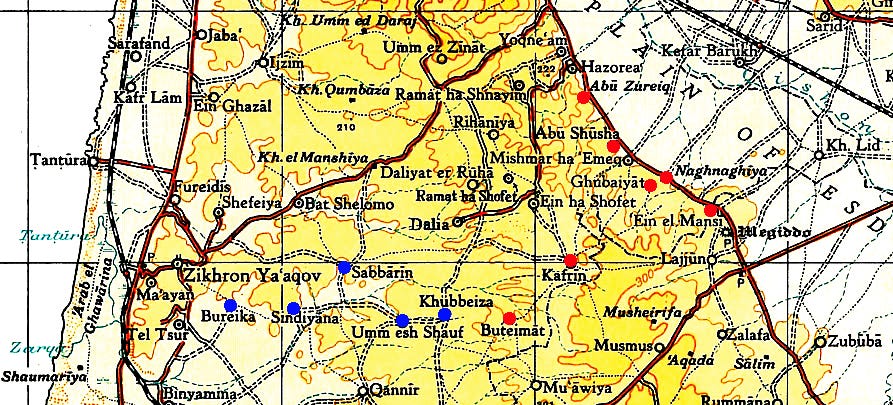

In one scene, we see Kabha leading a group of Arabic-speaking students through the ruins of Abu Shusha, overlooking Kibbutz Mishmar Ha’emek. On April 10, 1948, the Arab Liberation Army, commanded by the charismatic Fawzi al-Qawuqji, launched a devastating attack on the kibbutz. Using a brief ceasefire – granted by Qawuqji so that the kibbutz could evacuate its women and children – to rearm, the Haganah then retaliated, destroying Abu Shusha and expelling its residents. We learn about this dramatic turn in events by way of readings from Qawuqji’s logs and from the written testimony of a kibbutz resident, Adam Shadmi, both accompanied by rare movies from the time, and it’s difficult not to feel sympathy for both sides in the battle.

One of Kabha’s goals is to help Jewish Israelis understand what the Palestinian side went through, without feeling threatened by their own feelings of empathy. He knows that such understanding does not come easy, and that may explain in part the barely perceptible smile he often wears. It is accompanied by a mischievous tendency to tweak Zionist historians with their own facts and figures.

Thus, in Shoshani’s film, Kabha turns on its head the conventional wisdom that says that the newfound state overcame a huge numerical disadvantage in the War of Independence, citing figures from a book published by Israel’s Defense Ministry to the effect that, whereas all of the Arab forces fighting in the war amounted to no more than 35,000 troops, the Haganah fielded 67,000 fighters. According to Kabha, “the Jewish forces had a strategic advantage that was decisive and obvious.” In this way, he debunks what he calls “the ethos of the few versus the many,” smiling slyly as he asks an interviewer to “excuse me if I’m disturbing your ethos.”

Later in the same film, he calls explicitly on “the Jewish side” to become familiar with the Palestinian memory, and the role that the land plays in it. “’Every grain of earth here has a name in Arabic,’” he explains, adding that, “Moshe Dayan said that, not me!

Traveling northeast along Route 65 from Kabha’s own home village of Umm al-Qutuf to Umm al-Fahm, one arrives at that city’s art gallery in Umm al-Fahm, which last summer was tapped by the Ministry of Culture to become the country’s first Arab museum. It is home to another of Kabha’s projects: a historical archive of Wadi Ara. The gallery’s founder and director, Said Abu Shakra, turned to Kabha after he himself taped a series of interviews with his own mother before her death in 2009. Maryam Abu Shakra had lived through the Nakba, and although she could not read or write, she was an articulate oral witness of what she experienced during Israel’s founding and early years. This gave her son the idea of collecting the testimony of other veteran residents of the region, and for this he turned to Mustafa Kabha.

In the early decades of Israeli statehood, the Arabs who remained were not prone to speak about the traumas of the war or the years of military rule they were subjected to. Written documentation from the Palestinian side was also scarce.

Although he didn’t specifically set out to do so, Kabha told me in February, “you could say that I laid down the fundamentals of Palestinian oral history.” Initially, he quips, “People said that Mustafa Kabha interviews people who are senile.” Today, however, there’s acceptance of “oral history as a narrative for the weaker side in conflicts. In the eyes of the stronger, the weak side is [simply] numbers. I present the numbers as human stories.”

In Umm al-Fahm, Kabha trained a cadre of oral historians who, beginning in 2005, went out and filmed interviews with 600 locals, the majority of whom are now deceased. (The archive also includes thousands of historical photographs from the region, a collection curated by photographic historian Guy Raz.) As Kabha said in 2023 at the launch of a trilingual volume of selected oral histories from the archive, “Oral history doesn’t consist simply of interviewing someone and publishing what they say. It has to go through a scientific process of cross-checking, and because we present testimony in the language in which it was said, it also means knowing the local dialect.”

When I asked how he learned the skills of oral history-taking, he gave a surprising reply: “I went back to the sources, specifically the Islamic-Arabic sources, in the collection of hadith [accounts of the life] of the Prophet Muhammad.” The hadith, he explains, were selected and compiled during the first millennium after Muhammad’s death, by way of an exacting method of authentication called Al-Jarh wa l-tadil (crediting and discrediting).

Kabha believes in the need of not only Jews, but of Palestinians themselves, to learn about this history, and to do so with a critical eye. In his own book “The Palestinian People,” Kabaha is critical of the decisions made by the Islamist Hajj Amin al-Husseini during the decades that he dominated the national movement and stifled any opportunity for compromise with the Zionists. “A people that can’t look at itself critically is a handicapped people,” says Kabha.

Some 700,000 Palestinians went into exile during the Nakba, with those who remained numbering only 150,000. Nonetheless, says Kabha, “We have our uniqueness. We are citizens of a state that is neither Arab nor Muslim.... [but we] were perceived as cultural symbols, not only by all Palestinians, but also among all the Arabs.... [W]e led the formation of the general Palestinian narrative, and also led the Palestinian literary scene – Mahmoud Darwish was one of ours, Samih al-Qasim was one of ours. Emile Habib and Tawfiq Zayyad.”

Despite the special tension in Arab-Jewish relations that has characterized the recent period, Kabha remains steadfast in his belief in the possibility of attaining equality and mutual respect. Like others who deal with the subject, he speaks about “shared society” rather than “coexistence.” The latter, he believes, ultimately has the effect of “making permanent the differences between two separate groups, who encounter one another in a venue that is under Jewish hegemony -- eating at the expense of the kibbutz,” for example. “That doesn’t work. They need to meet someplace that is exterritorial, or at a location where they feel partnership or see eye to eye. They can begin in Hebrew, but should aim [eventually] to have their meetings also take place in Arabic. Therefore you need to aim to make Arabic a required language of study in the Jewish schools.

“This can’t be just lip service. Everything has to be shared. Not just to equalize budgets for road paving, but also natural resources. Everything. If an Arab hears that Israel has discovered natural-gas fields, he has to be a partner in it. Water too. You can see that Jewish communities, both here and in the West Bank, get it automatically, including water for [agricultural] irrigation. But not Arabs. The kibbutzim get water for agriculture, and we don’t, even when we’re in the same local council.”

Which brings us to the subject of politics, and Kabha’s role as spokesman of the Consensus Committee. The committee’s chairman, novelist, poet and public intellectual Muhammad Ali Taha, explains that it was convened for the first time in 1992, “first, to unite the Arab parties in one list, and second, to get more people to vote in elections.” Its efforts did not bear fruit, though, until 2015, when the four main parties representing Arab voters – Hadash, the United Arab List, Balad and Ta’al – facing new electoral rules that threatened to keep one or more of them out of the Knesset altogether, finally joined forces. And they were rewarded with an unprecedented 15 seats in the Knesset that year. But ideological and personal differences, and some meddling by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who helped convince Mansour Abbas, leader of the Islamist United Arab List, to go it alone, led to the first cracks in the Joint List in 2021 (following which the UAL actually joined the short-lived coalition led by Naftali Bennett and Yair Lapid), and its final dissolution before the 2022 election.

In fact, polling shows that the vast majority of the Arab public want their representatives to be part of the governing coalition, and to that end, want to see the Joint List reconvene.

The party leaders, however, remain split ideologically over the question. Muhammad Ali Taha describes the quandary: “The Islamic Movement of Mansour Abbas, they want to be part of any coalition. It doesn’t matter which one.... Hadash and Balad don’t want to be part, though they are willing to support [a centrist coalition] from outside.” (At the moment, it should be said, the question is moot, since even the opposition leaders who dared to invite Mansour Abbas into their government four years ago now pledge to boycott both him and the other Arab parties if and when they have the opportunity to form a government.) This is among the differences that the Consensus Committee is attempting to resolve.

Hadash’s Yousef Jabareen, who is not in the current Knesset but is widely expected to be elected the party’s new chairman after the promised retirement of Ayman Odeh, also believes that “today, we are closer to two lists than to a single one. That may more reliably reflect the differences that exist with [Abbas’] UAL on the issue of membership in a coalition. This is a matter of super-principle. To this day, I hear that in UAL they don’t rule out going with Netanyahu, and I simply can’t believe it.”

There is agreement, however, about Mustafa Kabha. According to Jabareen, Kabha is “a source of values and a symbol of the constant search for fairness and justice.” Both he and Taha separately referred to Kabha as a “walking encyclopedia.”

“This is my homeland the same way it’s your homeland,” Mustafa Kabha told me the first time we met, seven years ago. “I want to arrive at a point where you are reconciled to this and I am reconciled to it. I don’t want to be at a point where I come to lecture at a Jewish-religious high school, and the teacher tells the children that I love to hike the land, and the children ask, Where do you come off loving my land? That’s the most painful thing I ever was told, ever.”

If today Kabha knows “every tree, every bush and every plant” that grows here, he says he sees a day when “everyone knows these things. But for everyone to know them under the motto of a shared homeland, where I have a place.”