A non-reluctant pioneer

Alex Weingrod devoted a lifetime to understanding Israeli society. He did so by challenging the conventional wisdom, pursuing his career as an anthropologist at a brand-new university in the Negev.

It was mid-June, and I was engrossed in reading a book when my phone pinged, indicating an incoming Whatsapp message. Now that my concentration was interrupted, it struck me – and also surprised me – just how much I was enjoying what I had feared would be a difficult book to get through, a concise history of Israeli society called “The New Israelis: Ethnicity, Religion and Nationalism.”

The author, Alex Weingrod, had been in touch a few months earlier to ask if I wanted to take a look at the book and possibly write about it. Weingrod, an emeritus professor of anthropology at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, whom I knew a bit through a family connection, told me he had labored on the book for the past decade. He was now 94, and didn’t need to add that this was likely his academic swan song.

I took the copy he offered me, but was far from sure that I would be able to write intelligently about what is, after all, a scholarly book put out by an academic press. Thereafter, Alex would call every few weeks, to ask -- apologetically -- whether I had “any news” for him, and I would tell him -- apologetically -- that I was “still working on it” and would “be in touch.”

Eventually, it occurred to me that doing an interview with the American-born Weingrod, who began observing Israel at ground level in the 1950s, might be a way not only to cover the book but also to plumb the author’s knowledge and experience for insight into just how the country got to be where it is today.

Over the years, Weingrod’s topics of study had included the immigration and settlement in Israel of Moroccan Jews, nearly a quarter-million of whom arrived during the 1960s and early ‘70s; the related subject of the development among North African immigrants of the custom of visiting the graves of Jewish “saints” (“tzaddikim”); and an examination of the webs of interdependence that had evolved organically between Jerusalem’s otherwise segregated Jewish and Arab populations.

Having come up with an angle for a story – an interview -- and sensitive to Weingrod’s advanced age, I threw myself into reading “The New Israelis” – and that’s where I was, enjoying the book, when my Whatsapp pinged. What it bore was an announcement that Alex Weingrod had died, a day earlier, on June 17.

To my profound regret, I had missed the opportunity to interview Weingrod, but I decided that it wasn’t too late to write about his book and his career. What follows, therefore, is my attempt to do just that.

Alex Weingrod belonged to a generation of American Jews who came of age when the existence of the Jewish state still seemed miraculous, and most of them could identify with it irrespective of their particular political or religious beliefs. He was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1931, to parents both of whom had immigrated from Poland the decade before. They identified with Labor Zionism, and Alex himself was active in the Habonim Zionist youth movement.

In 1949-50, Alex participated in the Jewish Agency’s training program for Zionist youth leaders (the Machon Lemadrichim) in Jerusalem. There he met his future wife, Bracha Soloway. She had grown up in a Yiddish-speaking home in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and was affiliated with the youth movement Young Judea.

Both committed themselves to aliyah (immigration to Israel), but a practical-minded Alex returned to the United States for his academic studies – doing his B.A., M.A. and doctorate in anthropology, all at the University of Chicago – before settling in Israel. The fieldwork for his Ph.D., which he earned in 1959, was carried out at a Negev moshav populated by new olim from Morocco. (This work formed the basis of Weingrod’s first book, “The Reluctant Pioneers,” published in 1966.)

Weingrod then received an offer from the Jewish Agency to set up and head an applied-research wing within its settlement division, with the goal of identifying and proposing solutions to problems that came up among new immigrants. In the citation that accompanied the life achievement award Weingrod received from the Israel Anthropological Association in 2019, that undertaking was described as “an important attempt, and the first in Israel, to implement the insights gained from social research. It was also an outstanding effort to recruit the research and concepts of anthropology for the study of Israeli society.”

Alex also did some teaching at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, but when that did not lead to a long-term academic position, he and Bracha, herself an educator, returned to the United States, where he spent more than a decade teaching anthropology at Brandeis University. It was only in 1974 that he and Bracha, now with four children, returned to Israel, this time for good. (Bracha Weingrod died in 2023.)

Whether knowingly or not, Weingrod had entered a zone of academic and political controversy that would have implications not only for his career, but also for the national project of immigrant absorption, probably the newborn state’s principal raison d’etre.

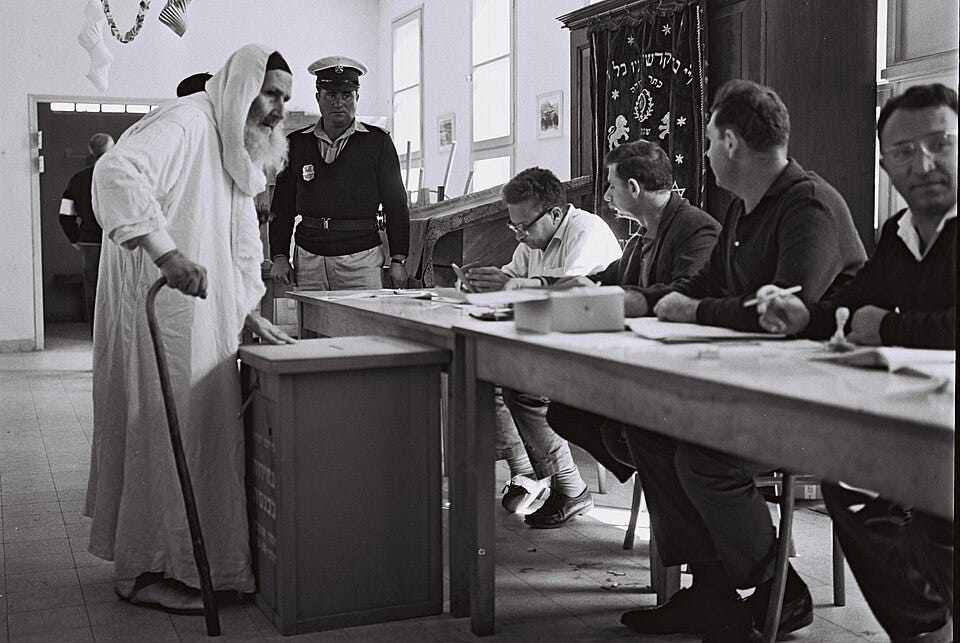

Israel took great pride in its “ingathering of the exiles,” which, within its first five years alone, required it to contend with a population that more than doubled in size. The prevailing ethos of the establishment was to view society as a melting pot, in which the newest arrivals, who were predominantly from North Africa and the Middle East, were expected to shed the customs and attitudes of their birthplaces and adopt the prevailing cultural norms of their new home. They did not behave according to the plan however, and among the consequences of the mistakes caused by the arrogance and mistaken assumptions of Israeli officialdom were socioeconomic gaps, and the accompanying resentments of succeeding generations of immigrants, upon which a political party (Shas) came into existence and changed party politics, for the negative, I would suggest.

As Yoram Bilu, emeritus professor of anthropology and sociology at the Hebrew University, and a longtime colleague of Weingrod’s, explained to me, culture was regarded at the time as analogous to “a dress, a garment that you could put on, and take off.” There were even professional terms to describe the process: “desocialization” and “resocialization.”

This approach characterized both the Zionist institutions that undertook the formidable task of receiving and providing for the new immigrants, but also the intellectual approach of scholars at what was at the time the new state’s lone university, in Jerusalem.

In his eulogy for Weingrod last month, cultural anthropologist Prof. André Levy traced the dominance of the melting-pot approach back to the influence of one of the Hebrew University’s towering figures, the sociologist Samuel Noah Eisenstadt. “Simply, in his understanding,” said Levy, “the cultural differences of the new arrivals were temporary – passing -- and thus could be expected to disappear over the years in a process of assimilation and acculturation.”

According to Levy, himself an expert on Moroccan Jewry in Ben-Gurion University’s department of sociology and anthropology, that philosophy “reflected a research trend that attempted to assist Zionist social engineering, by way of blurring or repressing the unique immigrant cultures.”

In Levy’s telling, “Weingrod strongly objected to the idea of the melting pot.... Culture [he believed] doesn’t disappear, but rather it changes its appearance; it continues to accompany the immigrants, serving as a source of value, meaning and identity.”

More generally, the Israeli academic world of the 1960s didn’t regard anthropology as a serious discipline. As Bilu explained, the sociologists believed that they were doing real science, whereas their colleagues in anthropology were practicing a “soft” version of science. By that, they meant that the latter’s research consists of “interviewing people, and observing them. That’s work that you can’t replicate, and when you do replicate it, the results are disastrous.”

Thus, when cultural anthropologist Weingrod returned to Israel as an immigrant, in 1974, there was no place for him at the Hebrew University. Instead, he found a position in the behavioral sciences department of Ben-Gurion University, then known as the University of the Negev, which had opened its doors in Beersheba only three years earlier. He spent the remainder of his career there, combining his own innovative with service as a teacher and mentor to many of the scholars who today lead the field of anthropology in Israel.

In an obituary published by several of his former colleagues on the website of the American Anthropological Association, Weingrod’s career was described as proceeding along “three interconnected axes: politics, religion, and especially ethnicity and ethnic inequality.” The colleagues, Harvey Goldberg, Fran Markowitz, and André Levy, went on to cite several examples of how his “ethnography strikingly shows how the theoretical hold of classic Zionist nation-building notions comes loose in everyday life.”

In an admirably candid essay from 2004, Weingrod acknowledged that there were times when the professional scholar in him found itself at odds with the liberal Zionist he was: “I sometimes find that I am studying Israeli events that are fascinating anthropologically, while, at the same time... devastating for my own politics as a citizen.”

Elaborating on this, he explained how “Mysticism and religious fundamentalism have... become potent national political as well as cultural forces. Reputed holy men take what appear to be effective parts in political-party election campaigns; amulets and rabbis’ curses are used in the attempt to shape political outlooks...”

And he went further: “The issues are made more complicated as some of the Sephardi political activists have attacked those who criticize these trends as merely a new form of Ashkenazi domination and discrimination: fundamentalism is a ‘form of resistance’, they claim, although in my reading this makes practically anything to be ‘resistance’.”

Five decades later, “The New Israelis” can be regarded as a parting gift from Weingrod. Not a memoir, it is, rather, a concise but comprehensive and up-to-date anthropological portrait of Israel. I think of it as his attempt to understand how we got to where we are today, in the positive sense as well as the negative. It is a scholarly book, conversant with the relevant professional research undertaken during the past half-century (and provides citations for it all, as well as a lengthy bibliography), but it is also highly readable. In it, Weingrod offers up a running critique of the conventional wisdom about life here, but delivers his message in a gentle and generous – and sometimes ironic -- manner.

Weingrod has chapters on how an earlier generation of political leaders tried to engineer Israel’s collective memory by arranging highly symbolic state reburial ceremonies: In 1949, it was the reinterment of Theodor Herzl’s remains on the mount in Jerusalem that now bore his name, and in 1982, the spectacle concocted by Menachem Begin in the Judean Desert for the burial of a variety of human bones that the prime minister had decided were the remains of the Bar Kochba fighters who died in a second century C.E. revolt against Rome. (The special irony of the latter event was that the Zionist movement had turned Bar Kochba, a failed zealot rebel, into a heroic warrior worthy of emulation. For more in that vein, I highly recommend Weingrod’s 1997 review of three books on “Memory, History and the Israeli Past” that he published in the journal Israel Studies.)

Other chapters cover Israel’s Palestinian-Arab population; the growth, diversification, and politicization of Orthodox Jewry; the rebirth of the Hebrew language; and even one that looks at the changes that popular music has undergone since the state’s early years. Some of these topics are obvious, others less so, but Weingrod’s analyses are usually novel and insightful.

Weingrod had already submitted a complete manuscript to Cambridge University Press when the current Netanyahu government was sworn in at the end of 2022. Less than a month later, that government precipitated a political crisis by initiating an attempt (still ongoing) to restructure, politicize and weaken the country’s legal and judicial systems. The “judicial coup” was followed by the surprise attack on Israel by Hamas, on October 7, 2023. Weingrod updated the text where needed, and wrote a new epilogue to the book, on “Israel’s Terrible Fateful Year,” in which he described the political and social earthquake that ensued from these events.

Clearly, Weingrod was shaken up by the outrages and shocks of 2023, although he maintains his professional tone even in this addendum. I would suggest, however, that in light of what Alex Weingrod tells us in the body of the book about the diverse, volatile and sometimes self-defeating society he spent a lifetime observing, neither of those events should have come as a complete surprise. He told us what we needed to know.

Thank you, David, for this fascinating and moving piece. I ordered the book from Adraba and look forward to reading it.

Beautiful.