'A nation of teachers in its tiny, luminous land'

Fania Oz-Salzberger has not given up on Israel -- at least not the humanistic Israel that her father believed in and fought for, a struggle that she has assumed as her own

Last month, Fania Oz-Salzberger -- a professor emerita of history at the University of Haifa and outspoken political activist who has courageously taken up part of the public-intellectual mantle that was held by her late father, the writer Amos Oz – addressed an audience on “Reclaiming the Humanist Legacy of Zionism.”

Talk about courageous.

Speaking at the invitation of the Younes and Soraya Nazarian Center for Israel Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, Oz-Salzberger offered not so much a defense of Israel at a time when it is under attack from many directions, but rather a reiteration of what she is certain were the original values and goals of the Zionist movement, and which she thinks can still serve as Israel’s salvation today.

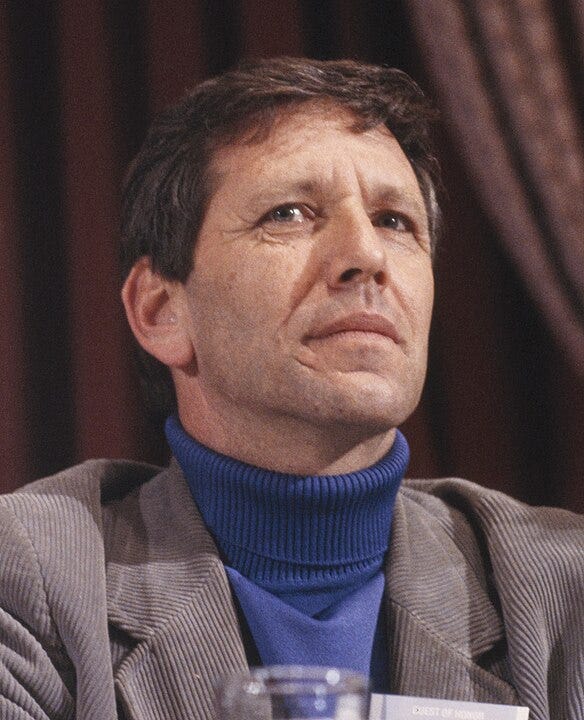

It would be difficult to exaggerate role played by Fania’s father in Israel’s cultural history. Amos Oz (1939-2018) was both a critically admired and commercially successful writer of fiction, memoir, journalism and literary criticism. Each October, during the final decades of his life, there was speculation as to whether he would finally become Israel’s first native-born recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature. (S.Y. Agnon won the prize in 1966, but he was a product of the Diaspora, born in Ukraine.) But Oz was much more than a brilliant author; he also was a living public conscience , who identified within months after the Six-Day War, in which he had served as a combat soldier, the need, as he saw it, for Israel to prepare for an eventual withdrawal from the newly “liberated” territories.

Amos Oz never stopped believing in the need for two states, Israel and Palestine, but he also remained a clear-eyed realist who did not delude himself or others about the challenges that Israel faced, both from without and within. The internal challenges have become far more pronounced in recent years, and have detracted from the solidarity so required to meet the external challenges that exploded in Israel’s face a year ago. But Oz-Salzberger remains committed to the universal, humanistic values that formed the foundation of Israel’s creation, and over the past year has been sharing her analysis and recommendations with anyone who is open to listening.

I suspect that there are many readers for whom her words will serve as a desperately needed tonic, a reminder of why it was natural for them to grow up loving and believing in Israel. It was from the beginning an imperfect Israel, but it always aspired to do better at living up to its founding values, rather than sufficing with the claim that it was the “only democracy in the Middle East,” even as it moved more and more distant from that description. She also raises the hope – it’s too general to be characterized as a plan – that what she believes are the half of Israel’s citizens who continue to share the humanist Zionist vision will succeed in reclaiming it.

Oz-Salzberger was originally supposed to deliver her remarks at UCLA in person, but the war led to the cancellation of her flight from Israel to Los Angeles, and so she spoke to her audience via Zoom. You can view her address here.

If you have seen recordings of Amos Oz, or had the privilege of hearing him speak in person, you may be moved to see the extent to which his daughter, who is 64, echoes his rhetorical style, as well as his depth of knowledge and thought. Her erudition, humanity and also wit make for an inspiring 45 minutes of viewing, and provide some compensation for the loss of her father’s voice from the public forum.

But for those who prefer the executive summary, I have tried to encapsulate her message here, in the hope it may serve as a tonic for bewildered supporters, even lovers, of Israel who find themselves wondering these days if the Israel they believed is salvageable.

Arguably, the key sentence in Oz-Salzberger’s talk was her declaration that “The Jewish nation-state is in my mind not an end, but a means to a higher end… Not an eternal goal — Jewish nationalism, statehood, nation-statehood,” but rather, the creation of a state that would guarantee “the thriving and survival of its citizens and neighbors” [emphasis added].

There are certainly forces in Israel today that look beyond the state as the be-all and end-all of the Zionist project, but what they have in mind is an ethnocentric and messianic vision that is based on a literal understanding of Jewish law, to the exclusion of universal values. What Oz-Salzberger proposes is the return to a set of values that hark back not just to the Enlightenment, but that she is certain had their origins in the culture of ancient Israel.

According to her, “historic mainstream Zionism was humanist at its core, because its claim to independent nationhood for the Jews was rooted in a wider recognition of the value of all human lives, dignity, belonging and civil self-expression.” Her father, she recalls, “used to say that the Zionist movement from its very cradle it was a coalition of differing dreams: the middle-class liberal Zionism of [Theodor] Herzl, the social-justice Zionism of the Labor Zionist founding fathers and mothers [including] A.D. Gordon and Berl Katznelson, the fiery Zionism of Zeev Jabotinsky and the Revisionists, and the legal-diplomatic approach of Chaim Weizmann.”

Despite their widely divergent beliefs, what all these Zionist streams, “including the Revisionists, ancestors of today’s erring, rogue Likud,” shared was the determination that “the state of the Jews would be a liberal democracy, a human rights-based democracy, a rule-of-law-based democracy, offering equality to all of its citizens, peace to its neighbors, and law-abiding membership in the international community. They also hoped that Israel would bring some good to the world, because Zionism was about that too.”

She doesn’t devote time responding to the accusations widely bandied about these days that the Zionist project is “settler-colonialist” -- “I’m not speaking to those ignorantly claiming Zionism is a satanic cult, I want to reach out to the moderates, including Palestinians” – but returns repeatedly to the need to acknowledge facts and truth, however inconvenient they may be. For example, Oz-Salzberger insists that it was the Palestinians’ rejection of the United Nations’ 1947 proposal to divide the land between two states that set the conflict on its ongoing bloody path.

“Let us remember that in that crucial moment,” she says, referring to November 29, 1947, when the nascent UN General Assembly passed Resolution 181, “Jews danced in streets, and Palestinians opened fire. What could have been a great moment of peacemaking, and [creation] of a new neighborhood,” quickly turned into a devastating war, at the end of which Israel was left “with larger borders, later internationally recognized,” and the Palestinians suffered the Nakba, “a tragedy for both nations, and after 76 years, a regional crisis turning global as we speak.”

(Her words echo one of the most memorable passages in Amos Oz’s memoir “A Tale of Love and Darkness,” in which he recalls, as an 8-year-old, witnessing how that night, in Jerusalem, “the bars opened up all over the city and handed out soft drinks and snacks and even alcoholic drinks until the first light of dawn… strangers hugged each other in the streets and kissed each other with tears, and startled English policemen were also dragged into the circles of dancers… and frenzied revelers climbed up on British armored cars and waved the flag of the state that had not yet been established yet, but tonight, over there in Lake Success, it had been decided that it had the right to be established” [translation by Nicholas de Lange] .)

It's important for Oz-Salzberger to mention this history, but she does not dwell on it, because it is not her purpose to use Palestinians’ decades of rejectionism as justification for contemporary Israel’s rejectionism. The latter, it needs to be said, includes not only the imposition over more than a half-century of an oppressive occupation regime, and Israel’s creeping annexation of the West Bank, but under the most recent Netanyahu governments, the explicit rejection of the very concept of Palestinian political self-determination.

Oz-Salzberger prefers to remind her listeners of what she sees as the crucial pragmatism of the state’s founding fathers and mothers: “The genius of Herzl, Weizmann, Ben-Gurion, Rabin, was to protect the Jews by achieving international legitimacy.” This it did by accommodating the existing circumstances, and by its readiness to compromise. In the end, the national project was realized because it was able to “slip through a small crack in history. Not to replace the Diaspora, but to realign the Jewish world around an Altneuland,” an “Old-New Land,” as Herzl entitled his 1902 novel envisioning the utopian society he envisioned coming into being in Palestine.

The Zionism of Israel’s Declaration of Independence, the state’s founding document, incorporated not only the values of “the Enlightenment, which reinvented universalism for the modern world,” but also “sought to highlight the morality of the Prophets, which is the most universalist and humanist part of the Bible – that and the social laws of the Torah. Social justice, compassion, the Jews as leaders and servants of world peace. Not as masters of war. Rather than conquerors and empire makers, a nation of teachers in its tiny, luminous land.”

Nonetheless, and this is essential to her worldview, she is insistent that, “Israeli democracy is worth nothing without security; Israeli security is worth nothing without democracy.”

Thus, her idealism is twinned with hard-nosed realism, and I was reminded again of her father when Fania, elaborating on her belief that a “Jewish nation-state… is not an eternal goal,” suggested the conditions that would make it possible to relent on that goal:

“Perhaps one day history will turn a corner, and the world will become a federation or confederation… or a global republic. This was the prediction of Immanuel Kant, admired by many Jews perhaps because this was the vision of the Hebrew Prophets, the world with nations, but all at peace, all belonging to the same community. And when that happy moment comes, I too will be happy to give up my nation-state for a Middle East confederacy or a world union – in that moment, yes, but not a moment before.

“We Jews have learnt the hard way, what it means to be a powerless minority in a world of brute force.”

(When I asked her, in a later email exchange, if she could foresee Israel relinquishing the Law of Return, which continues to offer to become a naturalized citizen to Jews and descendants of Jews exclusively -- not exactly the exemplification of liberal democracy -- she responded simply that “it is still requisite for Jewish existence in this day and age,” adding: “If a peaceful sovereign Palestine is founded, more or less within the pre-1967 borders, it can of course enact its own law of return within its borders.”)

Oz-Salzberger also makes no apologies for her humanistic, and in her case secular, approach to Judaism, explaining that, “We are one of very few nations in world for whom universal values have always been part of our national identity…. Our laws of Torah social justice, humanism shone bright from the very core of the Hebrew Bible. Universalism was and can still be our birthright.

In the war of 1948-49, Oz-Salberger reminds us, “One percent of all our population was killed, and no one called it genocide.”

“My Zionist forebears did not espouse either religious fanaticism, misguided progressivism, or nihilist chaos-mongering, and I will not tire of repeating that the Zionist movement at its core was not a disrupter: it offered a model and a bridge. The kibbutzim and moshavim offered a global model, while the Declaration of Independence offered its hand in peace to all its Arab residents, citizens, and neighbors. And promised equality to its Arab citizens. All this in the midst of a devastating war of independence.” In the war of 1948-49, she reminds us, “One percent of all our population was killed, and no one called it genocide.”

Oz-Salzberger referred with great warmth during her talk not only to the kibbutzim that were devastated by the October 7 attacks but also to the kibbutz as a concept. It is her belief, one only strengthened by the response of the kibbutz movement and its members to the crisis, that the kibbutz remains relevant and still has a contribution to make to Israeli society.

Fania herself grew up on Kibbutz Hulda, where her father, then called “Amos Klausner,” had picked up and moved as an adolescent (“And so at the age of 14 and a half, a couple of years after my mother’s death, I killed my father and the whole of Jerusalem, changed my name and went on my own to Kibbutz Hulda to live there over the ruins [“Love and Darkness,” page 464] .”) But considering the significant changes that the kibbutz movement has undergone over the past three decades, in particular the fact that a majority have moved from having a collective economy to privatization of many aspects of community life, I was curious to understand if her emotional comments about the kibbutzim went beyond romanticism and the sympathy elicited by the Hamas onslaught on October 7.

When we spoke by phone, she explained that though she was the first in the family to leave the kibbutz – “I left because I wanted an academic career… and the kibbutz slowed you down” -- “Part of it remained with me, and stayed in my heart, in a way that really opened up, especially after the October 7 disaster.”

Oz-Salzberger said she was particularly moved by the internal solidarity maintained by the affected kibbutzim: “It’s the only time in human history, as far as I know, in which attacked communities that had to leave, to flee, relocated intact as a community, and they have kept their kibbutz communities and solidarity, all this time, all this year.” At the same time, astonishingly, the same kibbutzim, which are the homes of most of the 101 captives still held by Hamas in Gaza, have been “vilified by Netanyahu’s government and cronies and spokespersons.”

She views the kibbutz as one of the “three best gifts that Zionism gave to the world, alongside the city of Tel Aviv and modern Hebrew culture – literature, cinema and art.”

Oz-Salzberger is well aware of the major changes undergone by the kibbutz model in recent decades, but believes that the changes have not been unanimously negative.

It’s jarring when she praises the kibbutz for continuing to be “communist,” by which she presumably means that the means of production of individual kibbutzim are still for the most part collectively owned.

“It was always a very humanist communism, of course, and was a wonderful rejoinder to the kind of East European, and Russian, Stalinist, Bolshevik, Maoist communism. It was a democratic communism. That part of what we used to call technical equality has gone down, naturally, because that’s human nature, but the part of sharing -- sharing community, sharing responsibility, caring for one another -- persists. A total social-economic network for people who weren’t going through the best times of their lives.”

So, Oz-Salzberger is optimistic about the future of the kibbutz movement. “For its community and individual solidarity, I think the kibbutz is here to stay, and October 7 has only made that stronger. Brought a lot of young people into this circle. People are deeply interested in joining, I’m told by friends in the kibbutz movement…. They may not be sharing everything economically, but they are deeply caring about each other socially.”

But she goes further than that, saying that she views the kibbutz as one of the “three best gifts that Zionism gave to the world, alongside the city of Tel Aviv and modern Hebrew culture – literature, cinema and art.”

When I press her a little more on the point (perhaps she’s a little starry-eyed?) in a follow-up email, she calls up a quote from Martin Buber, who “sagely called the kibbutz ‘an experiment that hasn’t failed,’ and this observation still stands. And yes, the kibbutz was one of the best suggestions that the Zionist movement has made to humankind.”

Beautiful portrait of an important figure. Come up one time to Zichron, David, and we can all get together