A momentous day...

A lifelong dream had finally come true, and the Umm al-Fahm Gallery was about to be upgraded to "museum" status. Then politics intervened, and the long-awaited moment was delayed

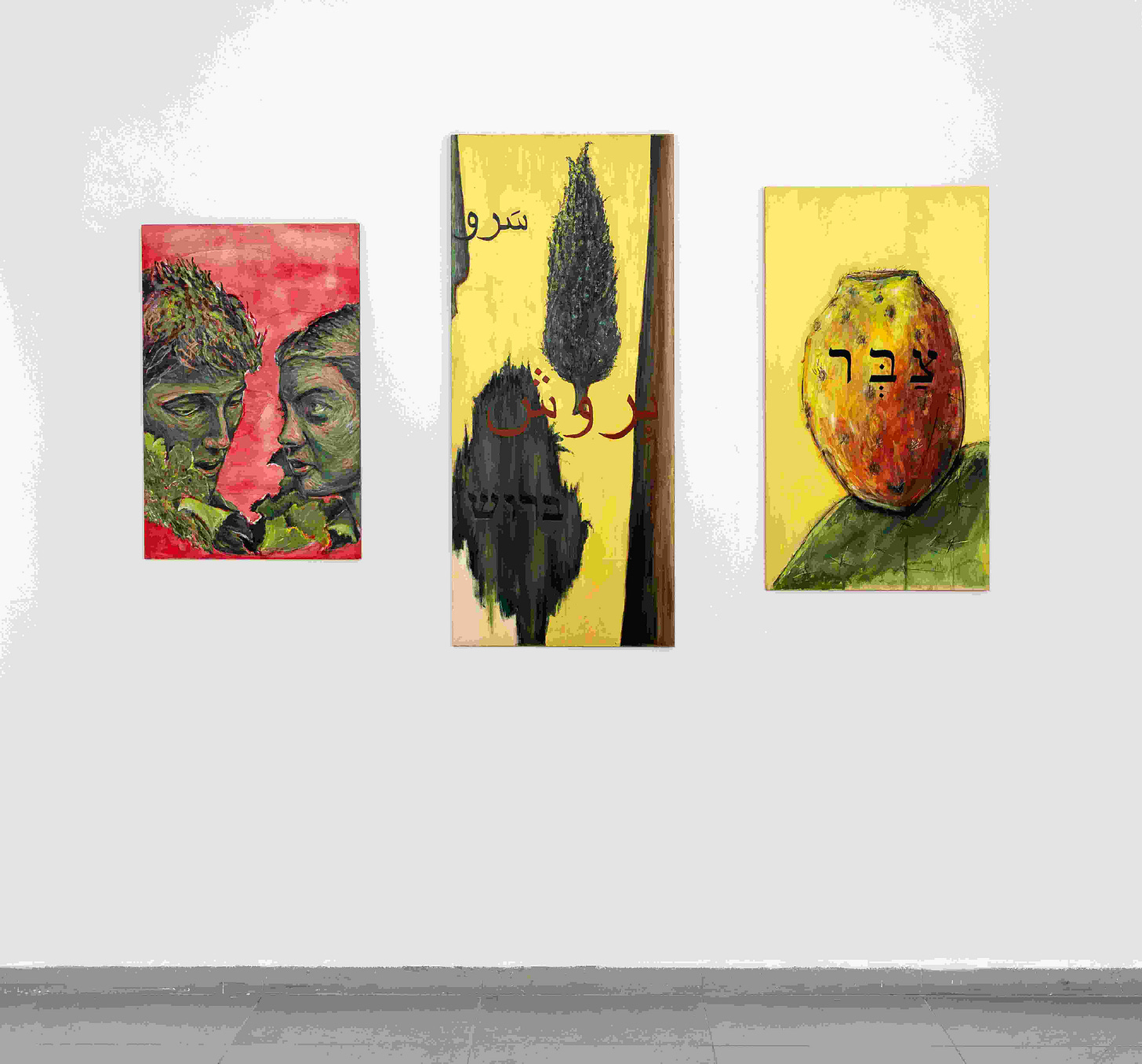

November 16 should have been a festive day in Umm al-Fahm, as the Arab city’s vaunted art gallery was set to mark its elevation to the status of museum, making it the first such institution in an Arab town to receive that recognition from the state. And indeed, that Shabbat was a momentous day at the gallery, with the simultaneous opening of six new exhibitions of contemporary art. Visitors wandered between the individual display spaces spread over the gallery’s three stories, viewing the new shows and hearing gallery talks by the individual artists and their curators. Then as many as could fit, crowded into the gallery’s small lecture hall for a ceremony led by Said Abu Shakra, the founder and director of the Umm al-Fahm Gallery of Art.

Abu Shakra introduced each of the participating artists, inviting them to make remarks, and presented with a potted cyclamen, the plant that is as ubiquitous at this time of year in Israel as poinsettias are in the United States. But there were no government ministers or officials from Umm al-Fahm city hall present, and in fact no ceremony officially marking the transition to museum. Abu Shakra acknowledged the change of plan, explaining that the inauguration of the new museum had been postponed until April. By then, he said, he hoped that the wars would be behind us, and a celebration would be more appropriate.

Almost since the day the gallery first opened, in 1996, it has been Said Abu Shakra’s ambition to turn it into a world-class museum of Palestinian culture and have it recognized as such by the state. That dream seemed finally to have been realized last July, when the Ministry of Culture and Sports announced that Umm al-Fahm’s bid had been the winner of a national call soliciting proposals for a museum. The prize would be an annual grant for a period of five years, during which the gallery could assemble and train professional staff, bring its physical plant up to code, and add to its permanent collection. At the end of that period, it was expected that the gallery would meet the national standards required for recognition as a museum.

Almost immediately on receiving the news, Abu Shakra swung into action, and within a day or two, he had scheduled the opening ceremony for November 16, and pushed back the planned opening of the autumn’s new exhibitions to that date as well. Israeli Jews, who make up a significant proportion of the gallery’s visitors, are often hesitant to venture to Umm al-Fahm, Israel’s third largest Arab city, and combining the two occasions would make a large turnout more likely.

When we spoke in September, however, two months before the scheduled event, Abu Shakra told me that over the summer he had encountered some turbulence in what should have been a smooth flight. Voices had been raised of people opposed to the selection of an art gallery as Israel’s museum of “Arab culture.” There were those who expected such an institution to present the Palestine narrative, at the center of which is the Nakba – the “catastrophe,” the Arabic term by which the Palestinians refer to establishment of the State of Israel -- which many of them feel continues to this day.

But there were also people from within Umm al-Fahm who sent both local and state authorities complaints about what they claimed were building violations that should have prevented even the gallery from operating in its present location.

When we spoke in September, I understood from Said that he had responded to all of the charges, and that once he had satisfied certain financial requirements from the culture ministry, it would be possible to sign a contract with the state, and the first allotment of state funds would be forthcoming. He had, it seemed, prevailed over the opponents, but he didn’t sound very happy. The complaints, he felt, had been an unnecessary distraction, and he seemed truly wounded by the fact that it had been fellow Fahmawis (as residents of Umm al-Fahm are called) who seemed to want to prevent him from realizing his life’s ambition.

When we spoke again in early November, shortly before the scheduled opening, the contract with the ministry was about to be signed, and Abu Shakra had found a new building a short distance from the museum’s current venue that he hoped would be ready to house the museum by late spring. Its advantages over the current space include an underground parking lot, something the gallery sorely lacks. But the opposition had not subsided, and included some anonymous efforts in the local community to blacken the name of the gallery and its director.

During the brief period when the “government of change,” led by Naftali Bennett and Yair Lapid, was in power – June 13, 2021-December 29, 2022 – it adopted Decision 550, a 30-billion shekel, five-year plan meant to address gaps in most every aspect of life in the Arab community, ranging from crime prevention to education to culture. That included a 360 million-shekel allocation for cultural projects.

When Chili Tropper, from Benny Gantz’s National Unity party, took over the Culture Ministry, his staff “undertook a very fundamental mapping of cultural life in Arab society,” explains Hen Dahan, who in 2021 was deputy to the ministry’s director general and the person who oversaw the process. What they learned was “pretty depressing,” he says, as it showed a lack of kinds of services and programs that were standard in Jewish communities. The ministry came up with a list of priority projects, and solicited proposals from outside entrepreneurs for establishment of a cinematheque, a repertory theater, as well as the naming of Arab “heritage” landmarks, and the buttressing of an existing Academy of the Arabic Language. The flagship project was to be a new museum of Arab culture.

This was not a case of the State of Israel setting out to create a museum from scratch. It was not equivalent, for example, to the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, D.C., deciding to add another museum to the 21 national museums it currently operates under the auspices of the federal government. And the funding that would go the winning bid was not intended (and not sufficient) for a building.

The November 2022 document announcing a call for bids was very specific in specifying what an application had to include: Its 80 pages went into precise detail about the technical standards required of the physical plant; the professional positions that needed to be filled for it to meet the standards of a museum, and a variety of economic guarantees that needed to be presented to insure its financial viability. As regarded the content of the institution, however, it didn’t go beyond saying it should “provide the state’s residents with, and serve as a home for, Arab artists and Arab culture.”

I asked Dahan if the decision to refer to “Arab” culture rather than “Palestinian” was a political one, intended to work around the growing unwillingness of Jewish society in Israel to acknowledge the unique identity of the indigenous Arabs of Palestine or to confront the central role of the Nakba in their collective identity. If anything, Israeli society has become less receptive to that identity in recent years.

“Not everything is political,” he responded, and I couldn’t tell if he was being disingenuous or not. “’Arab’ is far more extensive than “Palestinian.’ It includes Egypt and Syria and Jordan... There’s a very fine Arabic culture that isn’t political. There are Arabic language books, and films, and many many artists and great cultural wealth.”

True, of course, all of it, but in fact, the proposal that won the culture ministry’s tender was for a museum of contemporary Palestinian art. It’s not about the history of the Arabic language, and it doesn’t take in the Egyptian film industry or Arab music.

Hen Dahan explained that when it issues a tender like this, “we are essentially buying services, supporting a body for five years, so that at the end of that period, once it is viable,” it will meet the professional standards for a museum. That means it will have a fire-prevention system and a properly trained curatorial staff, and its structure will be wheelchair-accessible, for example, but doesn’t even get into the question of the subjects covered by the museum.

At least in the culture ministry that Hen Dahan worked for, “it wasn’t our job to be a censor of the conversation.” Israel has laws that prevent certain types of conversations, but it’s the law-enforcement authorities that take action when the law is broken. (Apparently the current minister, Miki Zohar, takes a more wide-ranging view of his authority, having decided recently to ban the public screening of several films that deal with the Nakba.)

When the ministry went through the candidates, then, it was looking for the organization that seemed the most likely to succeed in realizing its goals, but not necessarily passing judgment on the goals themselves. That being said, I have little doubt that a proposal to create a “museum of the Nakba,” however well thought out and advanced in its conception and development, would not have won the culture ministry’s tender.

In the case of the Umm al-Fahm Gallery, its development over nearly three decades has included its regular exhibitions, many of which are accompanied by publication of a trilingual catalog (Arabic, Hebrew, English), the creation of a permanent collection of close to 2,000 works of art, most of it by Israeli-Arab artists, programs for schoolchildren, and a unique historical archive, which includes 600 video oral histories of veteran residents of Umm al-Fahm and its neighboring communities in Wadi Ara. In many ways, the gallery does offer a Palestinian narrative, but it does so quietly, without drawing attention to its efforts.

So, while there may be critics who feel that the museum does not have a sufficiently explicit set of political messages, anyone who follows the gallery, reads its catalogs, and is familiar with its archive knows very well that the experiences and the sensibility of Israel’s Palestinian citizens are part and parcel of nearly everything that take place there.

Wanting to learn more, therefore, about the objections, I spoke with two prominent critics of the decision to award the museum franchise to the gallery, Mohamad Agbaria and Muhammad Mahamid. Agbaria is director of the local community center, and was himself awarded the culture ministry’s tender to create Israel’s first Arabic-language theatre company. Mahamid is a multi-media artist, and a longtime theater person.

Mahamid believes that any museum should tell “the national story of the Arabs of Israel,” and to his taste, the current gallery is “overly Israeli for the people of Umm al-Fahm,” by which he means, among other things that “most of the artists it shows are from Tel Aviv and the country’s center,” and also from kibbutzim, meaning Jews. On the factual level, that charge is incorrect, but there is no doubt that Jewish artists and Jewish curators are active participants in many of the gallery’s exhibitions, and that visitors to the gallery include both Jews and Arabs. Said Abu Shakra wouldn’t have it any other way, either.

To illustrate his complaint, Mahamid referred to an exhibition from “three or four years ago... of letters [Israeli] soldiers sent to their mothers during the Second Lebanon war, in 2006.” To Mahamid’s thinking, it was “problematic” to show that in Umm al-Fahm.

The show Mahamid was referring to was a 2013 exhibition, “Letters,” created by the American-Israeli artist Eugene Lemay, which displayed undelivered letters written by fallen soldiers with whom Lemay served during that war.

Asked about the exhibition, Said Abu Shakra explained that he had seen Lemay’s work in the U.S. and had found it “human and compelling.” Lemay, he said in a written statement, “wanted to… create a conversation with women who were mourning the loss of the sons in war, and his conclusion was that there is no difference between one mother and another when their children fall in a war.”

Clearly, Abu Shakra and Mahamid have different conceptions regarding the role of a museum, a difference that is only complicated and exacerbated by the fact that the museum in question is supposed to represent a minority population that exists in a state of mutual suspicion and fear with the majority. Mohammed Mahamid, though he expressed himself delicately on this point, apparently does not see a place for a work that presents IDF soldiers in a human light. Abu Shakra, who responded to a number of questions I posed to him with a written statement, explained his perspective as a curator:

“I am a big believer in having the museum represent other opinions, and other peoples and individuals. When I exhibit a work, the first thing that I look at is the professional level, and that is also what guided me in this circumstance. I can’t ask other people to demonstrate patience and understanding for my message as a Palestinian if I am unable to demonstrate openness and understanding and patience for the message of the other.”

Both Mahamid and Agbaria told me that they object to Abu Shakra being the institution’s director, because he served for many years as an officer in the Israel Police, which according to Mahamid, was, at the time (he retired from the force in 2004) , “very, very, very shameful” in Arab society, and according to Agbaria, remains “unacceptable today to the Arab public.”

Abu Shakra, needless to say, rejects that criticism.

He notes that during his 25-year career in the police, his two principal assignments were in internal affairs and in the youth division, where, in his final post, he was “the national youth officer, the first Arab to hold that position.” As far as he’s concerned, “if I were living my life over again, I would again choose to undertake those same tasks, and fight crime [among young people] and fight corruption among the ranks of the Israel Police.”

Abu Shakra claims that he welcomes the criticism, which “is legitimate, and it’s good that it is being sounded,” but in conversation, it’s clear that it has been painful for him to have come all this way, to have realized a dream for which he labored tirelessly for nearly three decades, and now to face such obstacles, especially when they come from his own neighbors in this tight-knit city where he has spent nearly his entire life. He invites them to engage with him in dialogue, and says he has proposed as much, to no avail.

For their part, the opponents say that they proposed having the municipality and the gallery join forces to create a museum together, which would include the existing gallery but go beyond that. According to Agbaria, Abu Shakra refused, and also went back on an earlier agreement by which the foundation that runs the gallery would appoint two or three representatives of the city to its board of directors.

Abu Shakra says he has in fact accepted the mayor’s appointment of two members to the board, with whom he looks forward to creating a “genuine link.”

From its very founding, when Sheikh Ra’ed Salah – founder of the now-banned Islamic Movement Northern Branch -- was mayor of Umm al-Fahm, the gallery has always worked with the blessing of and in cooperation with City Hall. That has been the case with the current mayor, Samir Mahameed, who won reelection last year with over 90 percent of the vote.

When I spoke with Mayor Mahameed earlier this month, he was clearly aware of the objections that were being voiced within the community, and no less clearly determined not to be dragged into a dispute. He confirmed that the city had asked to have two representatives appointed to the foundation’s board, but says that the municipality is “in on the project, and we are happy.” He added, however, that “we gave him [Said] support, and we also expect that he will give us his trust and support. And I’m hopeful that things will work out.”

I think it’s fair to give the last word to Said Abu Shakra. He has chosen to identify actively with both his Palestinian heritage and his Israeli citizenship. He acts as if these are not in contradiction to each other, a challenging position in the best of times, and an excruciatingly difficult one during the past year.

Here is how he explained his motivation in the written statement he sent me:

“I work for the cause of equality in the State of Israel. I work in the field of art in order to create mutual empathy, respect and appreciation. If I am accused of advancing these causes, then I plead guilty, and am proud to be someone who is working to create mutual respect and love between human beings.”

What a tumultuous journey to realize one’s dreams! Someday I hope to visit and explore this museum to reflect on all the drama and resilience it took to be born.